Zeitblick

- Series A HillAc Production |

City,

My City - Series Two Part 9 The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1956-1958 This story is dedicated to those of all nations who have braved the conditions of this last remaining wilderness on planet earth and whose faith and conviction has so far kept its pristine environment free from exploitation. Long may this faith & conviction endure.

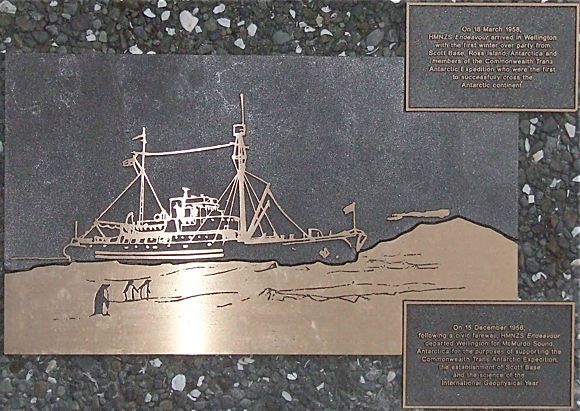

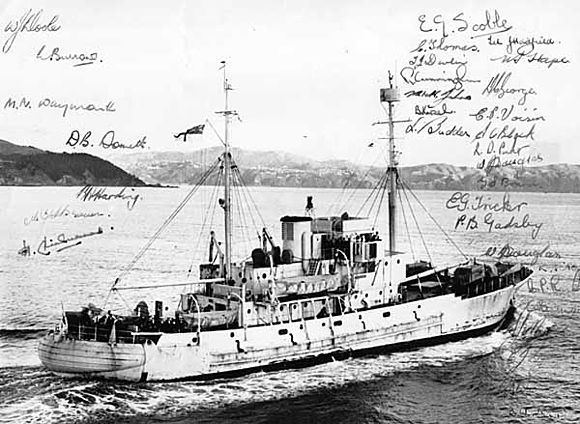

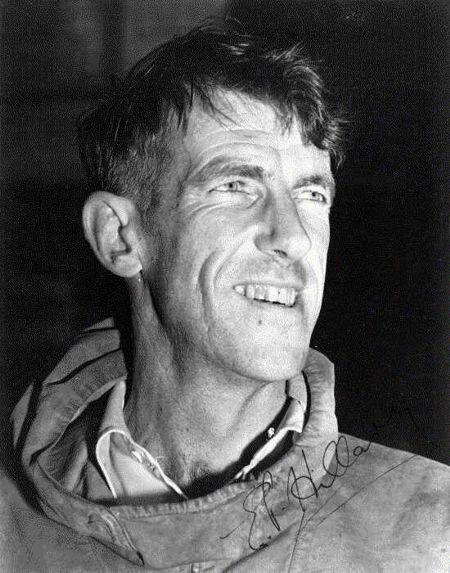

Just under 50 years ago, at 9am on March 17th, 1958, the diminutive Royal New Zealand Navy vessel, HMNZS Endeavour, sailed into Wellington Harbour at the end of an epic voyage from McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. For the city, the preceding weekend had passed stormy and disagreeable however Monday morning dawned fine and calm turning on, as only Wellington can do, a perfect Autumn day with bright sunshine and scarcely a breath of wind. On board the HMNZS Endeavour were the two heroes of the recently successful Trans-Antarctic Crossing, Sir Vivien Fuchs, knighted for his efforts in Antarctica, and Sir Edmund Hillary, knighted some years before for his remarkable ascent of Mount Everest. These two, along with their men were assembled on the vessels bridge keen to spot those waiting on shore, among them Lady June Hillary and Lady Eleanor Fuchs, who had come to meet their returning husbands. Snugly tied down on deck was much of the surviving equipment and transportation used by the teams during their arduous and dangerous trek, including one of the expedition's aircraft. In company with HMNZS Endeavour was the 1,957 tonne Danish-build polar ship Magga Dan, built in 1956 and utilised by Fuchs on his return journey to Antarctica with the stores and men necessary for phase two of the expedition. The expedition had been remarkably successful, the first crossing of Antarctica by way of the South Pole, and the first ever traversal of the continent using land vehicles.

In 1949 British explorer Vivian Fuchs conceived the idea of an expedition that would travel across the Antarctic Continent in a 3,200 km trek, passing through the most southerly point on the globe, the South Pole. It was not until 3 or 4 years later, however, that this idea became a reality when Fuchs was asked to draw up an initial plan. His strategy was to land and establish a base near the Weddell Sea on the Antarctic coast below South America. The team would over-winter at this base and, the following summer, strike out across the continent, passing through the South Pole and travelling on to McMurdo Sound on the opposite side of the continent. Early in 1955, under the patronage of the newly crowned Queen, Elizabeth 2nd, the British Government established a committee to facilitate this enormous undertaking and announced a grant of £100,000 towards its cost. Financial support was also provided by the Australia, South African and New Zealand Governments as well as from a host of other sources. The journey would take Fuchs through some of the harshest conditions and terrain on earth and in order to achieve his goal he would need to have bases set up at least for the second half of the journey from the South Pole to McMurdo Sound as his expedition would be unable to carry supplies for the whole trip. To this end the New Zealand Government assumed financial and organisational responsibility for what was to become known as the "Ross Sea Party" and appointed its newest hero, Sir Edmund Hillary, as its leader.

The Canadian vessel Theron, a sealer, was chartered to deliver Fuchs' party and its supplies to Antarctica. Sailing in mid-November to reach Antarctica during the southern Summer, she arrived at Vahsel Bay in January 1956 after having to force her way through brash sea-ice on the final stage of the journey. Here the party set up their initial base which they named Shackleton and commenced unloading supplies and equipment. Before the on-set of winter Fuchs returned to England in Theron to commence gathering stores and men for the next stage of the expedition. Meanwhile it was the responsibility of the eight men left behind to move the 300 tonnes of stores from Shackleton Base inland to firmer ground away from the dangerous and shifting sea-ice. This movement of supplies was not achieved without problems and during a fierce storm which raged for days, keeping the men confined to their only shelter, a storage crate in which the Sno-cat vehicles had been transported, they lost large quantities of supplies including coal, timber, a boat and 300 drums of fuel. Thankfully, however, all the food had already been moved inland. Fuchs returned to Antarctica on January 13th 1957 in the Danish-built arctic-ship Magga Dan. Once there he made his first priority the establishment of a site which they named South Ice and which was to be the launch-pad for their trans-Antarctic trek. Equipment and food were air-freighted to this site and exploration of the local area was undertaken.

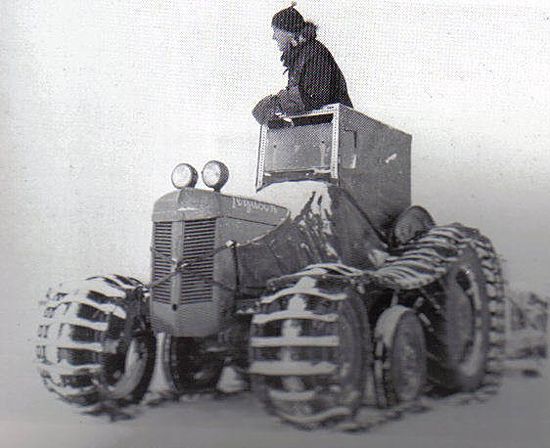

In the meantime far to the north, the Ross Sea Party were in Wellington pushing ahead with their plans and preparations to travel south where they were to establish a base named Scott Base in New Zealand's Ross Dependency. This party now included 5 scientists who would undertake a research program as part of the International Geophysical Year - 1957 to 1958 - and the original concept was thus extended far beyond the initial support party for Fuchs. It was to become New Zealand's first important foray into Antarctic exploration. A tight budget, however, would dictate that exploration and field work needed to be undertaken by dog-sled teams, supported by two aircraft. The generous loan to the party of 5 Ferguson tractors and two Weasel transport vehicles (a polar version of the Studebaker-built US Army transport from WWII) provided the necessary motorised transport needed by the team. What use, one might think, would a tractor be in the Antarctic waste, however a generous quota of that local do-it-yourself standby called Kiwi Ingenuity, saw these icons of the New Zealand farmyard turned into effective over-snow vehicles ensuring the success of the expedition. At the New Zealand Government Gracefield Stores, on the eastern side of Wellington Harbour (a former US Marine store), final preparations were being made for the shipping of stores and equipment. Individual kitbags were packed for each member of the expedition containing personal equipment and material they would need for the journey. Double-lined polar tents, pre-fabricated huts and all manner of equipment and apparatus needed to be prepared, tested and packed. Once at their destination everything must work perfectly as obtaining spares and/or replacements was out of the question. Even the pre-fabricated huts for the establishment of Scott Base were erected and dismantled time after time to ensure that, even in a blizzard, the men would know each beam and board and each nut and bolt.

At 11:00am on Saturday, December 15th, 1956 - the day of their departure - a civic farewell was held for the party in the Wellington Town Hall. This celebration, declared by Hillary and members of his party as the best send-off they were to receive, was attended by a range of dignitaries representing central and local Government, the Church and various Embassies as well as a range of naval and military personnel. Fittingly, in this instance, Wellington was represented by the then Mayor, Sir Francis (Frank) Kitts, after whom the park in which this commemorative plaque is displayed was named. At 1:30pm HMNZS Endeavour departed Queens Wharf witnessed by a large crowd of Wellingtonians as well as friends and relatives of those on board and sailed across Wellington Harbour to the Shelley Bay Naval Base to load explosives. Her route south, in company with a small flotilla of New Zealand and US naval vessels, took her to Christchurch, Dunedin and Bluff following which she sailed due south for the Ross Dependency. Endeavour arrived at McMurdo Sound on January 3rd 1957 and, almost immediately, air reconnaissance revealed to the party that Pram Point on Ross Island would make a more suitable site to build Scott Base than the one that had originally been chosen. Once established on the ice, Hillary's team set about exploring the surrounding terrain to determine an appropriate route up onto the Polar Plateau, over 1,500 meters above them. Following some alarming moments Skelton Glacier was selected as the best possible route and the party set about establishing supply depots at the bottom and, by air, at the top of the glacier, 290 kilometres and 466 kilometres respectively from Scott Base. The grand adventure was about to begin.

Hillary split his men and equipment up into three teams and, leaving the other two teams to explore the local area, he and three others set off with three tractors and the Weasel to climb Skelton Glacier and traverse the route Fuchs would take on the second part of his journey once he had reached and passed the South Pole. From the top of the glacier Hillary struck out towards the site of first supply base to be established, Plateau Depot, which had been established some days beforehand by air and which was reached by Hillary and his team on October 31st. With the air-freighted fuel and supplies securely established at the site, they set off again on November 8th continuing southward into increasingly difficult weather, hampering their progress while dramatically increasing fuel consumption. Just when things seemed hopeless weather conditions improved and they eventually reached an area suitable for the next supply base which, with typical Kiwi understatement, they named Depot 480. Hillary and his men, towing a home-made caravan on skis they called the Caboose, continued to motor south for long hours. One of the vehicles, the Weasel, finally broke down and its load of supplies and equipment had to be transferred to the tractors. On December 15th they reached the site for the final depot - Depot 700 - and within 5 days it had been fully stocked with supplies brought in by air. The task that he had agreed to undertake was now clearly over, however Hillary is not the sort of person to withdraw if he recognises a specific goal in front of him; be it the peak of a mountain, the achievement of what he views as the end of a long journey or the desire to visit the ends of the earth. To Hillary the South Pole met at least two of these criteria and he had already achieved the third. He had been working towards the pole for months and now, only 800 kilometres away, it was clearly within his grasp. His vehicles were in excellent working order, he had adequate supplies of fuel for the journey and he had nothing more imperative to do at that time. Although he had communicated his plans to his New Zealand Committee and to Fuchs, and neither, for whatever reason were keen for him to carry on, Hillary could see no reason why he shouldn't persist in exploring the rest of the route to the Pole on behalf of the British team. Should he arrive at the South Pole before Fuchs, well that would be a matter of good luck as it certainly depended on the weather and the terrain he would strike. As it happened he did strike bad terrain which began to take its toll on his vehicles and his fuel supplies to the stage where the continued operation of his vehicles and the success of his extended mission hung in the balance. Finally, after driving continuously southward for 24 hours in what they believed to be the correct direction, at 8:00pm on January 3rd, 1958, they spotted the flags of the South Pole. Within sight of their objective they camped for the night and on January 4th drove to the nearby American South Pole Station with exactly 91 litres of fuel left.

Those momentous events of January 4th 1958 have been described in Hillary's own words; I was swept into a confusion of congratulations, photographs, and questions, and then led off by friendly hands towards the warmth and fresh food of the Pole Station. But before I descended underground I took a last glance at our tractor train - the three farm tractors, tilted over like hip-shot horses, looked lonely and neglected like broken toys cast aside after playtime; the caboose...now seemed more like a horse-box than ever; and the two sledges had only the meagre load of a half-drum of fuel. Yes! There was no doubt about it - our tractor train was a bit of a laugh! But despite appearances, our Ferguson's had brought us over 1250 miles (2000 km) of snow and ice, crevasse and sastrugi [ice fields consisting of frozen ridges of snow making progress very difficult if not impossible] soft snow and blizzard to be the first vehicles to drive to the South Pole. Perhaps this last statement was behind Hillary's pressing desire to carry on to the South Pole? It is possible that once again, he wanted to claim a world first on behalf of New Zealand? Or perhaps he did choose to press on with a further 800 kilometres of exploration on behalf of the British Expedition? Yeah right!

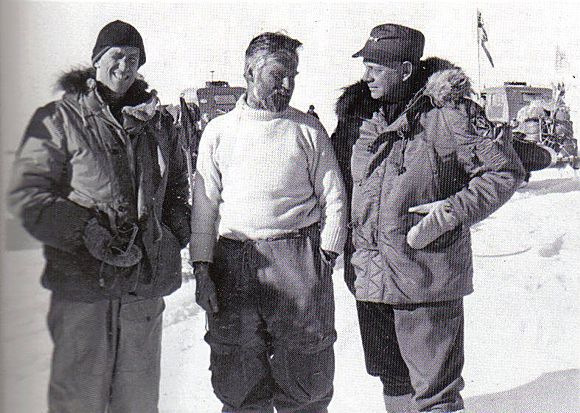

Meanwhile, after an extremely arduous trek, tested by bad weather, breakdowns, fields of sastrugi and crevasses, Fuchs reached the South Pole on January 19th, 15 days after Hillary. and his team. On their triumphant arrival, Fuchs and his team were greeted by Hillary, American Base Commander Admiral Dufek and a crowd of over 30 other people from the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Five days later, on January 24th Fuchs and his party started out again in what was to become a race to reach Scott Base before the southern winter closed in. The first base established by Hillary - Depot 700 - was reached on February 7th and it was here that Hillary joined the Fuchs party. Their perseverance paid off and the depot at the top of the Skelton Glacier was reached by the end of February. A few days later, at 2:00pm on March 2nd 1958, with vehicles decorated with all available flags and bunting, Fuchs and his men arrived at Scott Base. They had travelled 3,472 kilometres in 99 days, completing a spectacular and extraordinary journey. © Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |