|

Zeitblick

/ Das Online-Magazin der HillAc -

1. November 2008 - Nr. 31

|

|

City, My City |

|

|

Series 4, Part 2 The Garden in the Heart of the City This story is dedicated to Sir James Hector scientist, visionary and humanitarian whose imagination and drive played a significant role in the establishment and early administration of the Botanic Gardens. It is also dedicated to my late Grandmother, Catherine Elsie Lynette Wells (nee Mackenzie), who throughout her life had an enduring passion for gardening and plants and whose favourite bloom, like Dr Hector, was the rose. Having experienced two world wars in her lifetime, the "Peace" rose was always Lynette's favourite. "...such gardens are not made

We stroll through the gardens along broad boulevards lined with colour, down narrow winding paths that curve enchantingly around the hillsides and plunge in amongst huge trees, many well over 100 years old. Around the next corner we encounter a burst of tulip colour - a brilliant splash of yellow while those around them, their glory fading, have passed their "best before" date. In the valleys we hear the muted tinkle of a stream, crystal clear water tumbling down to the shores of the distant harbour. This was part of the original water supply for the young city of Wellington. Wide swathes of lawn merge into shaded, fern filled gullies and everywhere brilliant sprays of Rhododendron colour in red, pink and orange. And always the paths; avenues to explore, walkways that invite discovery and trails to new delights. Here is order and calm in the middle of this busy city. Here is escape and contentment for the mind. Here is brief peace.

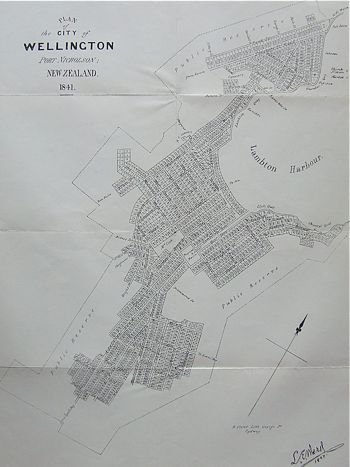

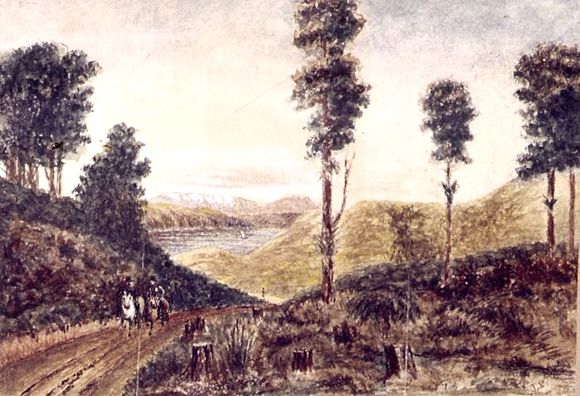

The city of Wellington has a Latin motto - "Suprema a Situ" - meaning supreme in location. This motto is so very appropriate as one surveys the magnificent sweep of the harbour along the shores of which lies a city conceived 170 years ago and half a world away in the gritty streets of London. It is to the visionaries and dreamers of the New Zealand Company, formed in Britain in 1839, who we must truly owe the existence and location - supreme as it is - of Wellington. But there are other things in this fair city which are attributable to those men of long ago. In the city design a need was identified for the inclusion of public reserves, broad bands of green to separate the "town lands" or the urban sections from the "country lands", the rural sections from which many of the early immigrants would make a living. In the original 1839 plans these broad public reserves encircled the city sweeping from the seashore in the north-west of the city, up and around into the surrounding hills and then back to meet the seashore again at the south-eastern edge of Lambton Harbour. The city was quite literally surrounded by a belt of green. Although almost stripped bare of trees for firewood and building timber in the years following colonisation, the determined and capable efforts of luminaries such as Sir James Hector saw that the reserves were re-planted and what remained of the native bush retained where this was possible. Most of the area which makes up this original "green belt" still remains and Wellington City is blessed with views of green-clad hills from almost every vantage point within the city.

Although the gardens were not physically established until 1868, the agent for the New Zealand Company, Colonel William Wakefield, was charged with the responsibility of ensuring the formation of Wellington's "green belt" and with setting aside land for a botanical garden within the public area of the city as early as 1839. This was to be an area of just over 12 acres (subsequent surveys suggest that it was closer to 14) and would run along a valley outside the city bounded on its west by Glenmore Street on its east by the hills of Kelburn. In 1851 the Wellington Horticultural Society, formed in 1841, began to press the Government, at that time situated in Auckland, to designate the area as a botanical reserve. As may be typical of many Governments then and now nothing happened. Instead in the following year, 1852, the Government granted part of the "town belt" adjoining the Botanic Gardens reserve to the Weslyan Mission for educational and religious purposes. As the Mission failed to develop this land as required in their contract with the Government it was returned to the "town belt" but the formation of the garden remained some years away. By the 1860's town milk supplies had become severely stretched, demand not being met by existing supply, and there was also a shortage of land on which to graze transport animals. Acting on the advice of his Council, Governor Thomas Gore Brown granted the land of the Basin Reserve (now Wellington's iconic cricket ground) and the "town belt" to the Superintendent of Wellington to be held in trust "for the purposes of a public utility to the Town of Wellington and its inhabitants". This move effectively transferred these lands, including the botanic reserve, into the care of the Wellington Provincial Government with legal right to use it as they saw fit. The land was split up and leased to 31 individuals but with stringent limitations concerning its use and the erection of any buildings. The Provincial Government retained the right to regain control of the land if they so decided. They did.

In 1865 the seat of the New Zealand Government was moved from Auckland to Wellington after a board of commissioners in Australia decided that Wellington would better meet the needs of central government because of its geographic location at the centre of the country and its excellent harbour. While perhaps not a decision that Aucklanders would have welcomed at the time they may now be thanking that Australian board? In conjunction with this move was the need to appoint an overseer to look after the grounds of the new Government House and its associated Domains and R H Huntley, one time school teacher, was appointed to the position. Huntley was a keen gardener and, from his letters, seemed to be very enthusiastic and even awed by the power he now wielded. He felt that he would need to be "...very exacting in claiming my proper privilege as head of a Department...". Like Hector he became increasingly concerned at the damage being done to the reserve by squatters who were removing large amounts of native bush and even erecting more than one building which was against the conditions set down by the Provincial Government 1852. Huntley petitioned Central Government to issue a Crown Grant to the Superintendent of Wellington to prevent any further damage and this was eventually done under the Public Domains Act of 1868 which was extended to include the Botanic Reserve. A nursery was established and Huntley was made responsible for raising trees and shrubs. To further his desire in to establish a garden reserve in Wellington he enlisted the aid of James Hector, the recently appointed Government scientific consultant who had moved from Otago to Wellington two years before. On Hectors examination of the area for the proposed garden, he was overwhelmingly positive on the appropriate choice of the site and on October 31st 1868 he was appointed to manage the establishment of the gardens with the help of R H Huntley. One positive aspect of Hectors management was the extension of the area already set aside by recommending the purchase of a portion of the adjacent Weslyan Reserve to establish a public park in conjunction with a garden for botanical and horticultural purposes. Such was the import of Hectors vision that this is precisely what the citizens Wellington enjoy today. Both Hector and Huntley will be remembered for their key roles and driving enthusiasm in the establishment of the Wellington Botanical Gardens.

Aside from the vision of Sir James Hector, the original objective of the garden was threefold providing benefits for Government, science and for the community. The purpose of the gardens was stated as i) providing a trial ground examining the economic potential of plants and in particular trees for forestry; ii) furnishing a garden for the collection and study of indigenous flora and exotic plants and iii) offering the citizens of Wellington an area for recreation and leisure. Early in the development of the gardens the first two objectives, and in particular objective number one, were given priority. Exotic seeds, especially those of conifers, were imported and raised in the garden nurseries. The importance of developing other varieties of trees to suit New Zealand conditions was seen as a priority by Hector who was deeply concerned about the clearance of much of the country's native forest. He believed this would lead to a future shortage of timber. In addition there was a need to develop trees suitable for use as shelter belts in wind prone parts of the country and to ensure an on-going supply of firewood. Two of these varieties, imported from California, were the Monterey Pine - known in New Zealand by its Latin name of Pinus Radiata or as White Pine - and the Monterey Cypress - known here as Macrocarpa. These trees grow extremely well in New Zealand conditions and the White Pine, especially cultivated here to grow tall and straight, is now our major species for construction timber. Interestingly when the original American species in California was threatened by disease, New Zealand disease resistant varieties were imported back into the United States. By 1875 over 120 different varieties of conifer had been established in the gardens and, although not all survived, there are significant examples of plants covering many species, some of which today are over 125 years old.

In 1874 the balance of the Weslyan Reserve was added to the gardens taking the total land area to over 60 acres or approximately 25 hectares. In 1886 Hector established a Teaching Garden for educational purposes and gradually over later years many of the beds were re-planted with seasonal plantings which gave a year round display of pleasure to visitors to the garden. A modern example of this is the celebrated tulip display which occurs in spring each year providing wide carpets of colour in a dazzling variety of hues from almost black to bright sunshine yellow. In 1889 the Wellington City Council approached the Government with a proposal to transfer management of the gardens from the New Zealand Institute to the Council as the withdrawal of Government funding for the gardens from 1885 had created difficulties with their maintenance. The upkeep of paths and fences and the eradication of gorse (furze) which had recently invaded the gardens was proving difficult without this financial support and transferring control of the gardens, it believed, would ensure their further development and maintenance. Through the New Zealand Institute the Council was already providing the majority of funding for the gardens and they felt that they should also have some control over this expenditure. The Government agreed and in 1891 the Botanic Garden Vesting Bill was passed transferring management to the Council. Included in this bill was an allowance for a 6 acre site for a future observatory and a stipulation that the original 13 acre garden reserve be maintained as such in perpetuity.

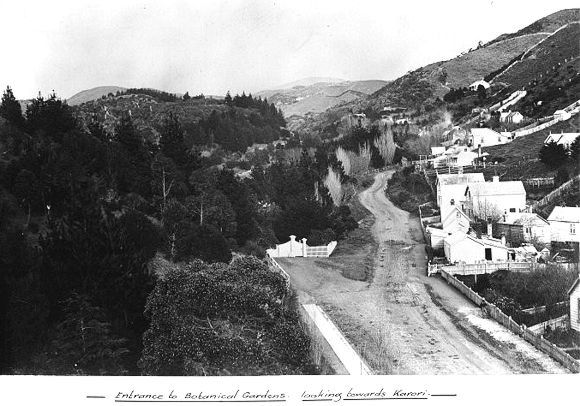

Many events and improvements have happened to the Botanical Gardens over the last 100 years to make them a favoured place for Wellington's citizens and tourists to visit. In 1883 George Vernon Hudson discovered a colony of glow worms along the Puketea Stream which flows into the duck pond within the gardens. These glow worms are still able to be viewed today. From 1948 recommendations were advanced for a rose garden to be included within the Botanical Gardens and in 1950 work was commenced on the Lady Norwood Rose Garden which remains a popular and beautiful feature of the gardens today. To the north of the rose gardens, adjoining the Bolton Street Memorial Cemetery, is the Anderson Park sports ground where sometimes carnivals are held during summer months. An extension to the Lady Norwood Rose Garden, built in 1960, was the Begonia House which, from 1989, included the hot house and Lilly Pond where giant water lilies bloom amongst blue and gold tropical fish. To the east of the gardens surrounded by shade trees is The Dell, a secluded area where garden visitors might enjoy a picnic or a game of catch and where the Teddy Bears Picnic is held annually. Above the Dell is the entrance to the gardens by way of the Wellington Cable Car which has travelled up the hill from the city since 1902.

Inside the gardens, along William Bramley Drive, is a small pagoda within which is a park bench providing a sad final footnote to this story. It concerns the death in 1891 of a brave young lad, William John Morris aged 12 years. A brass plaque affixed to this bench is dedicated to the memory and heroism of William who lost his life in an attempt to save his younger brother, Joseph aged 8, from drowning in Wellington Harbour. On July 30th 1891 both boys decided not to attend school and instead went to the harbour reclamation at Thorndon to play. Whilst there Joseph fell in and William, who was an excellent swimmer, dived in to rescue him. A worker named Brown pulled Joseph, quite exhausted, from the water by his ankle but his older brother was nowhere to be seen. Once young Joseph was on dry land he looked into the water and saw his brother lying on the seabed and although four nearby men plunged into the water to rescue him he was quite dead by the time they reached him. It is appropriate that William's heroism and selfless act of bravery is quietly commemorated in this peaceful corner of the city. © Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |