|

Zeitblick

/ Das Online-Magazin der HillAc -

15. Januar 2009 - Nr. 32

|

|

City, My City |

|

|

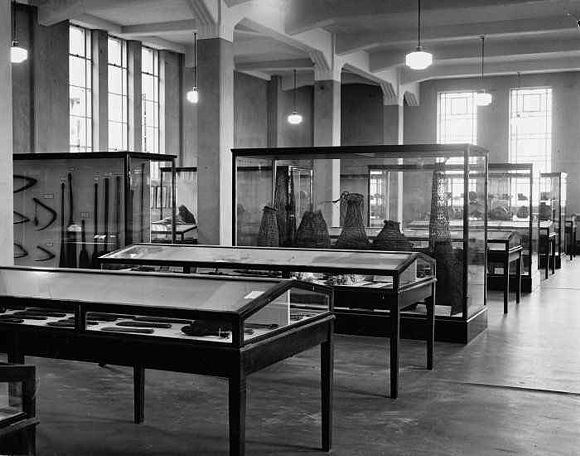

Series 4, Part 3 The Dominion Museum - Then & Now As with our last story concerning Wellington's Botanic Gardens, this story is also dedicated to Sir James Hector scientist, visionary and humanitarian whose imagination and drive played a significant role in the establishment and early administration of New Zealand science and of the Colonial Museum which became the Dominion Museum and eventually transformed into the present day Te Papa - The Museum of New Zealand. I well remember from my earliest childhood the spacious halls of the Dominion Museum in Buckle Street, stretching on tip-toes to look into the glass-fronted display cases, marvelling at artefacts from every corner of the world and of being so enthralled. "When I was growing up, my mother would take me to plays and museums,

European New Zealand began life in the very early years of the 1840s. Assuming one accepts the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi as our founding document then this date is February 6th 1842 but in fact New Zealand had come into being some time before that. The launch of a colonising expedition from London in 1839 to the site of present day Wellington could very well be considered the first formal British colonisation of this land. Those immigrants brought with them not only a desire for a new and better life but also a dream to implant the culture, art and heritage of Britain into this south seas land. Inherent in this desire, as with all other British colonial acquisitions, was the mapping of the new land, a study of its geology, an analysis of its anthropology and an assessment of its historic legacy and importasnce in the world. In such countries as New Zealand - "Little Britain" - most of this scientific research was undertaken by "imported" academics from the Home Country, from Europe and occasionally from Australia and the United States. One of these "imported" academics was Sir James Hector, born in Scotland in 1834. James graduated in medicine from the University of Edinburgh but soon showed an interest in and capacity for geology, botony and zoology. He honed these skills as surgeon/geologist on the Palliser Expedition to western Canada in 1857, following which he was elected fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and fellow of the Royal Geographic Society.

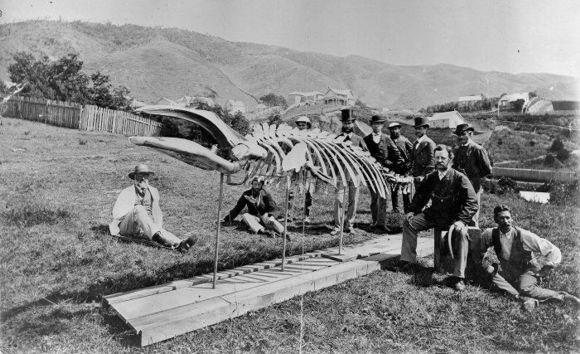

In 1861, on the recommendation of Sir Roderick Murchison who he had known from the Palliser Expedition, Hector was appointed to the post of director of the Geological Survey of Otago. Having the ability to utilise and enhance the talents of those who worked with him he employed three key people to assist in the survey - W Skey, J Buchanan and R B Gore. By September 1862 Hector and his team had extended his exploration throughout Otago Province, collecting as he went a large collection of rocks, fossils and minerals. The following year Hector extended his exploration to the West Coast of the South Island, carrying out as he did a dual crossing between Dunedin and Milford Sound and later, in 1865, he was involved in the New Zealand Exhibition in Dunedin. The extent and success of his work brought Hectors name and abilities to the attention of Central Government, recently relocated from Auckland to Wellington. A persuasive man by nature, Hector was successfully able to convince the Government that he was indeed the man for the job and was appointed director of both the Geological Survey and Colonial Museum in Wellington. Dr Hector immersed himself in the work of the Geological Survey thoroughly mapping the structure and natural composition of New Zealand as well as setting up of the Colonial Museum. As was reported in the Evening Post of October 4th 1865: "The internal fittings of the Colonial Museum near to Government House, are almost completed, and a large quantity of the curiosities are already distributed. Men are busily engaged in preparing the ground about the building for the plants, and a new fence is being prepared to take the place of the dilapidated one now standing. The Curator hopes to have the Museum open to visitors in the course of a short time." The museum itself was established in a small wooden building in what is now appropriately called Museum Street. Of course buildings were not large in those days and building in brick had been seriously avoided since the earthquake of 1855. They were more on a human scale one might say. Soon the building in Museum Street was to be accompanied by the residence of James Hector and one can see from the picture below the care and attention to detail he lavished on his garden as he had lavished on Wellingtons Botanic Garden.

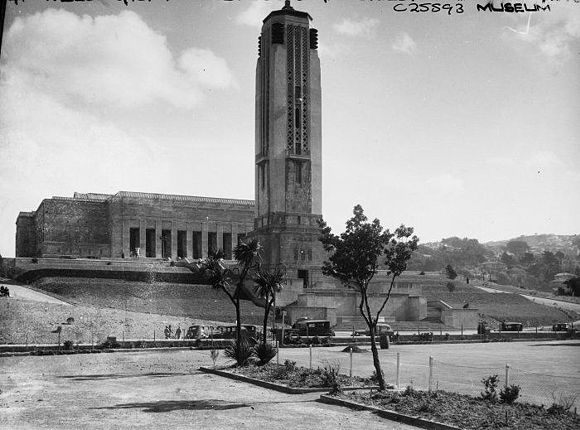

The "small building tucked in behind parliament" and its Director Sir James Hector provided a lengthy and excellent service to the people of Wellington over a period of some 40 years. In 1903, at approximately the age of 70 Hector retired as Director and was replaced by Augustus Hamilton. It was not long after this that in 1907 - coincidentally the same year in which Sir James Hector died - New Zealand became a self-governing Dominion within the British Commonwealth. Naturally it became sensible to change the name of the museum from "Colonial" to "Dominion" to reflect this revised political status of the country and the question of new premises was raised as many of the exhibits owned by the museum could not be displayed and were stored away in its basement. By 1908 government officials were looking at housing the museum in the former Mount Cook Police Barracks but this building - still in existence - would have been far too small, not much larger, in fact, than the existing museum building it was to replace. By 1910 plans to build a new museum were under development, the proposal being, as stated by the Honourable David Buddo, Minister of Internal Affairs, to "...make the Dominion Museum (the new building) large enough to accommodate the whole of the exhibits which are now under lock and key in the old museum." However, as with the best laid plans of any government, vacillation, arguement and financial constraints played their part and it was to be 1936 before the new premises were ready for occupation. The Auckland architects Gummer & Ford submitted the successful design for the new museum which included a War Memorial Carillon and a building large enough to accommodate the National Art Gallery as well as the museum. This impressive building remains to this day, occupied by a campus of Massey University while the Carillon chimes are played daily during the summer from 12:00 mid-day. The road in front of the Carillon, Buckle Street, now forms part of the busy arterial route thorough the city from the airport to the northern motorway exit from the city.

Providing entertainment and enlightenment for many of my generation, as well as those before and after, the Dominion Museum dominated the Mount Cook skyline for almost 40 years. But times change and an act of Parliament in 1972 (with effect from 1973) changed the name of the museum from Dominion Museum to National Museum with the potential for widespread impacts in the future. By the late 1980's the National Art Gallery, co-habiting the building with the museum, felt urgent need for a move from what it considered an inadequate building to protect the artistic treasures entrusted to it. Such lobying as undertaken by the National Art Gallery was unsuccessful but it did raise to Government awareness the need for a serious resolution to the current situation for both the art gallery and the museum. Although a much loved place the aging decreasing attendance record of the museum in Buckle Street seemed to indicate that, with changing attitudes towards the display of the identity and history of New Zealand (however widely this was accepted), the National Museum needed a new persona. This persona was to "...speak with authority about who we were and who we are; and what could at the same time communicate a sense of involvement, pride and community." The result was Te Papa Tongarewa, loosely translated as "Our Place". In 1988 the government set up a Project Development Board to investigate all possibilities and by 1992 an act of parliament had established the right to existence of the Museum of New Zealand - Te Papa Tongarewa.

An intensive development covering five years saw this impressive building open on February 14th 1998 on time and within budget - an achievement that all project managers aspire to and few achieve. Around the world such national muesums have usually been in place for a long time - in some instances for centuries - and as such they tend to exhibit the social values and ethics of that generation. With Te Papa as it is locally known, an opportunity was presented to the creators to develop a reality from an idea, something concrete from something etherial and something indeed from scratch, a place unique to New Zealand. This place is Te Papa Tongarewa - this place is Our Place.

© Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |