|

Zeitblick

/ Das Online-Magazin der HillAc -

29. Oktober 2009 - Nr. 35

|

City,

My City |

Series 4, Part 6 Wellington Public Hospital A legacy of service to the community This story is dedicated to my father, Robin Mackenzie Wells, who spent much of the last years of his short life in Wellington Hospital. As a child I well remember walking the long, vinyl-floored, corridors of Wellington Hospital to visit him and of being captivated by the obscure signs over many of the doors and of the arrows directing visitors to hospital wards where all manner of illnesses and ailments could be treated. I remember, too, the care that was afforded to my Father by the nursing and medical staff during his time there for which we as a family will always be grateful. It was in Dads nature to always think of others before himself and for our sake he delighted in making soft toys from the kitset's available for patients at the hospital. Two such items, a black ''Scottie Dog'' and a ginger ''Teddy Bear'', remained with our family for many, many years afterwards. I must admit that, whilst I was a child with no understanding of such matters, Dad always seemed fine to me. He would go to hospital and then return, until that one night when he was taken there from our house in Paekakariki, and did not come back. My father died in Wellington Hospital on August 30th 1965 at the young age of 41 and it is a cruel reality that the very drugs and procedures that would have extended his life, or indeed have cured him, were brought onto the market scant years after his death. For the care and attention afforded my Father and to the staff then and now of our Wellington Hospital - thank you. A short history of medicine:

Fittingly expressed in the quotation over the above picture, the advancement of medical knowledge through the ages has been one of development based on experiment, development based on learning and ultimately development based on mastery. In medicine, as in all things, we are where we are today because of those who have gone before. When the first settlers arrived in Wellington the art and application of surgery under anaesthetic and many of today's more modern treatments were little known, however the benefit of a building dedicated to healing and the quiet convalescence of body and soul, a hospital, were well known. Britain was renowned for its institutions of healing, both for those who could afford it and for those who couldn't. A history of Wellington Hospital must commence with the arrival of Wellington's "First Fleet", the first organised immigration to Wellington in 1840, under the New Zealand Company. It is a fact that a hospital of sorts did exist in Wellington soon after the early colonists arrived as, under the sponsorship of the New Zealand Company, administrative and accommodation buildings were built on the foreshore at Petone. These included premises for a school and for the New Zealand Company Infirmary, otherwise known as the ''Company's Hospital''. Like other buildings constructed in those helter-skelter days of early immigration this was probably a hut of local design built from ''raupo'' or bulrush grass. The treatment provided by the ''Infirmary'' was undoubtedly beneficial to 17 year old Amos Burr who arrived in Port Nicholson as a naval cadet on the survey ship Cuba in early January, 1840. It had been Amos job to prime the cannon and fire a salute to celebrate the completion of local land purchases by the New Zealand Company. The cannon failed to fire and while Amos was withdrawing the ball to reload the gun it discharged catapulting Amos into the water. Immediately he lost both forearms, one being completely blown away and the other almost entirely severed. According to Amos own testimony, he floated on his back until he was rescued by a man in a boat. He was soon back on board the Cuba where the ships surgeon, W. G. Haddy, treated him by removing the almost severed arm and stemming the flow of arterial blood. In those days such wounds were usually covered with tar but tradition has it that the cook saved Amos life by covering the stumps of his arms with salt, which probably acted as a natural antiseptic and hastened the healing process. The New Zealand Company looked after Amos very well and he remained in its care for some time at the infirmary - the ''Company's Hospital'' - on the Petone foreshore. By late February 1841 Amos had been discharged from the crew of the Cuba and continued to be supported in the infirmary at the Company's expense. A letter sent by William Wakefield to the Company's Head Office in London stated that "The boy wished to stay here [in New Zealand] and I have allowed him ten shillings a week with occasional clothes, but shall wish to be instructed how far this is to be continued. The expense already incurred in this matter amounts to £37-10s-10p. The boy is, I am told, entitled to £18 per annum from the funds of the Merchant Seaman's Society. Perhaps an arrangement with Mr Somes can be made for remitting the amount to him here, then he will be able to support himself". Considering the length of the return journey to London and back it would have been over 8 months before Wakefield received his instructions. This first hospital within the Wellington region had certainly confirmed its worth as the experience of Amos Burr proved. Regardless of what has been written in recent times, the exertions of the New Zealand Company were largely honourable. Over intervening years many have derided the actions taken by the New Zealand Company, particularly in these recent decades of political and cultural correctness, but the viewpoint of that day (ie mid 19th century) must be taken into account when questioning or understanding the actions of the Company. As there is no question that at some time during the 19th century the islands of New Zealand would have been colonised, would it have been better for the colonising nation to have been French, Belgian, Dutch or German? Reflecting on such a range of possibilities, would we not, therefore, prefer the status quo?

During the years 1840 through 1847, when the first purpose-built hospital was established in Wellington, there were many calls for such an institution to be provided for the township and for its citizens. The population was increasing rapidly and so too did the demands for a dedicated hospital. Over this period one of the foremost protagonists for the establishment of an hospital in Wellington was the newly arrived colonial surgeon Doctor John Patrick Fitzgerald, consulting surgeon to the Company's infirmary. On May 5th 1840 Dr Fitzgerald submitted a heart-felt plea to the people of Wellington through the local newspaper, the New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator, in which he directed "...the attention of the Colonists to the founding of an Hospital." He stated that "...the New Zealand Land Company humanely provided a temporary Infirmary for the reception of invalids from their ships;". Nothing unfortunately happened for a number of years following Fitzgerald's entreaty, certainly nothing of a positive nature. Decisions on hospitals in the first colony and future capital of New Zealand seemed to be at an impasse. Most knew that the establishment of an hospital was important, indeed necessary, but none could decide on the best way of funding it. Why does this remind me of present day New Zealand and government funding for a public health service? Differing opinions were expressed as to who should fund the hospital and who should best benefit by its establishment. Many of these views were stated in local newspapers in the garrulous language of the day, often giving rise to tit-for-tat debate between those who felt they had an opinion to express and those who felt they had a right to counter that opinion. The newspaper for June 12th 1841, after reminding the New Zealand Company that it had "...guaranteed the emigrants medical assistance, should they need it on arrival in the Colony" threw down the challenge to Wellingtonians to provide a public hospital by stating that ''An Hospital has been now established some months at the Bay of Islands, and if that small community is able to sustain an Institution of the kind, there can be no doubt the inhabitants of Port Nicholson are yet more so''. The newspaper went on to say that the Agent for the New Zealand Company [William Wakefield] ''...has volunteered a most liberal contribution to the funds of the Hospital...'' and that the New Zealand Company itself had ''...liberally offered to assist this object by providing a house, and an adequate supply of beds and bedding for the patients." Wakefield went on to suggest that ''...several of the medical gentlemen of the place have honourably offered their services gratuitously...'' to the proposed Hospital. The newspaper questioned the veracity of this understanding, suggesting that the education of said doctors and surgeons represented a large expenditure on their behalf of capital and time for which no remuneration had been received. Therefore the local newspapers, perhaps also expressing the beliefs of the local populace, considered that it would be unreasonable to expect the medical men to provide their services free of charge or in return for a small and limited gratuity from local authorities. Fund raising under these conditions was therefore considered unreasonable, whilst it was also doubtful that the New Zealand Company had intended to appear quite so generous. Several alternative suggestions were put forward by the newspaper which included: 1) Gathering annual subscriptions from those entitled to ''...act as Governors of this Institution...'', and that the Institution might expect the donation to it of ...''sums or things equivalent in value, far surpassing the amount required to qualify a person to fill the honourable office of Governor." 2) The utilisation of local members of the clergy to preach sermons "on occasions" to play on the compassion of the local population. 3) That the principle of user-pays be introduced to "Allow none to be received gratuitously, but let it be declared that all who avail themselves of the advantages of the Hospital, are received subject to a daily charge of so much per day while there."

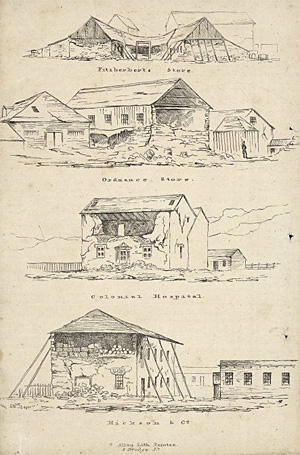

Over the years public meetings called for action to be taken on the question of the establishment of an hospital. For instance the meeting held on November 27th 1844 had the stated aim of "adopting such measures as may be necessary to the establishment of an HOSPITAL for the destitute sick in the District, when the attendance of those who feel desirous of furthering such an object, is earnestly requested." Eventually, in 1847, the authorities of Wellington approved the erection of an hospital at Thorndon and, with the co-operation of local Maori who gifted the land near present-day Pipitea Street, things got under way. Sir George Grey, Governor of New Zealand at that time, stressed his belief that such institutions should be available to Maori and Europeans alike to forge a bond of friendship between the two races. Such was the case with Wellington's first hospital which was opened on September 15th 1847 by Dr Fitzgerald while a Mr and Mrs Jacobs were appointed as hospital attendants. Short-lived though it might have been the new Colonial Hospital was not without its historic milestones. Apart from being Wellington's first permanent hospital, it saw renewed harmony between Maori and European, created greater understanding by Maori of the benefits of personal hygiene and was the location of the first ever operation undertaken in New Zealand under general anaesthetic - the removal of a tumour from the shoulder of a local Maori chief. Patients came from Rangitikei in the north, Wairarapa in the east and Queen Charlotte Sound at the top of the South Island. It is unfortunate to record, though, that the first patient to be admitted, Rebecca Branks, a local resident who had been injured by a tree felled by her husband, died of complications of tetanus. Either way, Wellington had its first hospital, large and superbly functional and fit for the purpose. It was, unfortunately, build of brick which was to prove disastrous just over a year later. At 1:40am on the 16th of October 1848, in the middle of a severe gale accompanied by very heavy rain, the fault line along the Awatere Valley in Marlborough, across Cook Strait from Wellington, ruptured along at least 105 kilometers of its length. The force of this breach caused the land around it to move 8 meters horizontally creating an earthquake of magnitude 7.5. Violent shaking ripped through the township throwing down many of the more inflexible buildings and causing damage to houses, the barracks, the jail and rendering the colonial hospital uninhabitable. The materials used for construction in the old country, brick and stone, were to prove not at all suitable here in quake-prone Wellington. It is interesting to note in the following picture of the day that the wooden structures surrounding those brick buildings badly damaged or destroyed remained practically unscathed. Understandably the next hospital was to be constructed of wood.

Prior to the unexpected destruction of the first Wellington Hospital, the other local newspaper, the New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian, was effusive in its praise of such a worthy institution. Its reporters were provided with a tour of the new hospital in late October 1847, and wrote: "Through the kindness of Dr Fitzgerald we had lately an opportunity of inspecting the Native Hospital on Thorndon Flat, which has been some time completed and open for the reception of patients. On the ground floor there is a large surgery, opposite to which is another room used as a sick ward, with convenient offices: on the first story is a large ward the length of the building, with vapour and other baths. It is eventually intended to add two wings to the present building, containing four wards capable of affording accommodation for sixty additional patients. When we visited the institution it was dinner hour, and three patients were sufficiently convalescent to sit down to dinner. Each patient on admission receives a warm bath and is afterwards placed in a comfortable bed with blankets, sheets, &c. On being sufficiently recovered to leave his bed the patient is supplied with warm clothing until he is pronounced by the medical officer to be well enough to be discharged. Any one who has seen a Maori pah and is acquainted with the native habits cannot fail to be struck with the contrast presented by the patients in this institution to their former way of living. The comfortable and well ventilated rooms, the cleanliness, regular diet, and warm clothing, to which the great majority of natives are unaccustomed must contribute no less to their speedy recovery than the care and medical assistance they receive"....."There are at present half a dozen Natives in the Hospital, chiefly from Waikanae and Otaki; one of them is the native chief who lately had a tumour removed from his back, of which we gave a short account, and who will be sufficiently recovered in a few days to leave the Hospital. The benefits of the institution are not confined to the natives, several settlers having since the opening of the Hospital applied for and received assistance." For almost five years following the great earthquake, Dr Fitzgerald continued to provide medical assistance to the wider Wellington community and local Maori from the remains of the partially destroyed 1847 building, facilities which were understandably cramped and far from suitable. He continued to lobby the newly established Wellington Provincial Government based on his belief that preventive medicine was of even greater importance to both local populations than was that of curative medicine, a belief rather advanced for that age. Also at this time Fitzgerald had his own personal tragedies to deal with. His wife, Eliza, died on April 4th 1852, 3 weeks after the birth of their 5th child, another daughter died of a heart ailment and Fitzgerald himself survived an attack of cholera. So much was going on in his life that, in order to try to deal with it all, he applied for a leave of absence which was caustically declined. In the meantime a new hospital of 40 beds and constructed of wood had been built to replace the ruined 1847 building. This new facility would have been a joy to Fitzgerald but, having been subjected to his recent personal ordeal and still exposed to the unfair taunts of officialdom, he couldn't take any more and resigned his post on July 31st 1854. Although accused, again unfairly, of the dereliction of his duty Fitzgerald, much to the disappointment of the Wellington populace and local Maori, never set foot in the country again.

The new Colonial Hospital, constructed on the site of the former, was to serve the citizens of Wellington for the next 20-something years. It was everything that the young city could want - centrally located to serve the community, constructed of wood to better withstand earth tremors, larger than the previous hospital providing 40 beds rather then the previous 16 and its floor-plan covered only one floor, removing the need for patients and staff to negotiate stairs. It was also surrounded by landscaped gardens which provided a pleasant aspect for recuperating patients. But this apparent Eden was not all it seemed. The advent of a Provincial system of government into New Zealand in 1852 effectively split the country into 6 virtual "fiefdoms", each controlled by a Superintendent who presided over a Provincial Council, a group which assumed the responsibility for control, maintenance and funding of all public services and institutions, including Wellington's hospital. For more than 20 years the Provincial Council's penny-pinching financial policies had a direct impact on the hospital by retarding its growth and limiting the facilities and services it could provide. Inept financial planning and the frequent withholding of funds, meant that financial allocations were seriously underestimated. By 1857, a mere 4 years after the new hospital was opened, the new Superintendent, Dr Alexander Johnston, was reporting that the "...walls and woodwork of the hospital were dirty and unsightly, for want of painting and whitewashing...". It was also reported that the water pump frequently broke down. Because of the persistent inaction of provincial government members this situation continued until 1872 leading to warnings about the insanitary and dangerous condition of the hospital. Still nothing was done and in the following year a typhoid epidemic swept through the city and the hospital killing 4 and resulting in 28 cases of infection. Speaking of a hole in the hospital roof, Dr Johnston was forced to complain "...I look forward with anxiety to the coming winter, when, I fear, every rain will saturate the wards, and every sunny day will draw out unhealthy exhalations from the decayed timber of the building." Continued requests for improvements fell on deaf ears and the hospital and it's facilities fell far behind the standards set by the rest of the world. The study of antisepsis and the importance of a sanitary environment, the introduction of vaccination and the establishment of specialised fields of medicine had made huge inroads in the development of medicine and surgical practices overseas but not so in Wellington. Funds were still very tightly controlled providing budgets that scarcely covered day-by-day operational costs, let alone anything left over for research and advancement. As things were rapidly drawing to a head, two events occurred almost simultaneously which would lead to a resolution of the problem. In April 1875 Wellington architect Christian Julius Toxward presented a plan for the construction of a new 112 bed hospital on a site in the southern Wellington suburb of Newtown "...on a rising surface, with plenty of fall for drainage...well sheltered from the south-east winds by a range of hills..." and in 1876 the much disliked system of Provincial Government came to an end, no doubt to the immense relief of those charged with the responsibility of running Wellington's public facilities. Interestingly enough, in AD78, the great Roman philosopher and orator Cicero had railed against any system of provincial government when speaking of his experiences in governing Rome's outlying territories. Said povinces were remote and ruled by hand-picked members of the Roman upper classes whose administration was upheld by the Roman army, a formula ripe for venality and corruption. Isn't it interesting how we seem to be unable to learn from history?

The design and location of Toxward's new hospital was approved in 1875 but construction did not begin until 1878. The 12 acre site in Riddiford Street, which remains the location of Wellington Hospital today, provided not only a site for the hospital but also its building materials. A special brick-making machine was imported from the United States and the clay for these bricks was dug from the construction site itself by convict labour from the nearby Terrace Prison. The labour gangs were marched daily from the prison above Wellington Terrace to Newtown and back, an average return distance of just over 8 kilometers. It has been estimated that some 4 million bricks were manufactured on-site to build the hospital and, following the construction of the building, plasterers came in to cover the bricks with a plaster veneer. Unfortunately the plastering job was delayed because of the shortage of tradesmen which was overcome by bringing plasterers across from Australia. The new hospital consisted of a two-storeyed block at the front centre containing the administration offices and resident surgeon's quarters, while the rest of the complex stretching behind occupied a single floor. Although concerns were expressed in a local newspaper about the transfer of patients, particularly the elderly and infirm, to the new hospital, this was successfully accomplished between June 27th and July 12th while the hospital itself was officially opened in June 1881. A grand ball was held on June 20th, 1881 to commemorate the opening and to gather donations towards the "Hospital Convalescent Fund". The Evening Post of June 21st described the ball in very eloquent terms and it seemed that no end of effort had gone into preparing rooms within the hospital to accommodate the many expected guests. Selected passages from the newspaper will paint a picture of that elegant evening in the young city, barely 40 years old - "Between the Hospital and the tramway on Adelaide Road - a distance of a few hundred yards - numerous vehicles of diverse descriptions plied on the arrival of every tram; but as the night was calm and fair, many preferred to perform the short journey on foot, especially as the road was adequately illuminated by means of a line of lamps"; "Then there were two small rooms on the opposite side of the corridor which were devoted to the use of lovers of cardplaying, while at either end of the passage refreshment bars were erected. The assemblage was estimated to comprise close upon 500 ladies and gentlemen"; "...dancing was kept up with the greatest possible spirit for many hours. The scene, indeed, was one of animation and splendour. Many of the ladies' costumes were of a complete and costly description, and in elegant taste"; "The lighter delicacies remaining from last night are to be given to the present inmates of the Hospital, while the more substantial viands are to be distributed among the poor of the city". Of course nothing remains in its original state, particularly when associated with a growing city, and within a few years of the opening of the hospital it was realised that accommodation for additional nurses would be required. Scant years following the hospital's grand opening the first of many additions was to be built and in July 1885 plans for the proposed two-story building - accommodation for 21 nurses on the upper floor and a ward for 22 children below - were drawn up by the Government Architect Mr Beatson. The need for more suitable accommodation for the nurses was taken seriously, very seriously. Two of the best nurses at the hospital had given notice that they were to leave because over accommodation issues. They had complained that once they finished their duties they did not have a sitting room to relax in and were obliged to go straight to bed to keep warm. One month later, on August 31st 1885, the plans were approved by the Hospital Trust House Committee and construction was soon to commence but then, on the other hand, perhaps it wasn't. Shortly after planning approval had been obtained it was suggested that this new building could provide accommodation for paediatric patients which was also being considered. Revised plans were ready by early December 1886 but their approval was to be delayed by concerns that the £1,000 already set aside would be exceeded. Hospital trustees agreed to make up the difference and eventually in March of 1887 the plans were approved, with the building being completed by June 1888. The development of the complex of dedicated medical facilities that was to be Wellington Hospital was under way and Dr Fitzgerald would have been pleased if somewhat annoyed that it had taken over 40 years to get to this point.

Although early 20th century additions to the hospital complex had been made in 1904 (a new nurses home), 1905 (separate accommodation for the aged and incurables to prevent existing ward space being used) and 1906 (a tuberculosis annex to treat patients suffering from what had recently become a more thoroughly understood disease), by 1908 it was obvious to the Board of Trustees that piecemeal improvements to the hospital would achieve little in the way of real growth. It seemed wiser, therefore, to consider a broad plan of improvements over subsequent years undertaken in phases. Early 1908 saw the issue of an invitation to submit designs for a new hospital complex, one of the particular specifications for which were the inclusion of a Children's Hospital and an Isolation Ward. It was also specified that the successful design would allow for development in stages but that the completed result would be an integrated hospital complex. Twenty plans were submitted with the tender being awarded to local architects Alfred Atkins and Roger Bacon trading as Atkins & Bacon. The estimated cost of these alterations and additions was £30,000. A further seven acres of land away from the main hospital but adjoining the existing acreage were obtained for the erection of an isolated Fever Hospital with a separate administrative block while within the hospital grounds proper a new Children's Hospital was to be erected to replace the rather dilapidated former ward. Government grants, often short of the mark, required that further public fund-raising was required. This was to lead to a particularly stormy altercation within Wellington between the producers of a public play who had pledged the proceeds of their performance to the hospital fund and a local minister, the Very Reverend Dr James Gibb. Gibb believed that the play was "satanic" and that it had "...appeal to the basest passions." The producer, entering into attack mode, won the day by donating the plays proceeds to the hospital fund. The Children's Hospital was completed in early 1912, but in a final assault, Reverend Gibb suggested that the name of the hospital, "King Edward VII Memorial Hospital", was appropriate as it was named after the 'naughty' Monarch. There was no doubt that the early 20th century, the Edwardian years, were responsible for a decade of advance and expansion for the hospital. Six new buildings were erected and the1909 "Hospital & Charitable Institutions Act" brought a wide range of hospitals, old peoples homes, sanatoria and medical facilities under the control of a single Health Board. The health facilities available to Wellingtonians were not only expanding, they were also contracting, providing a broader range of services via one source, the government Health Board.

Throughout the balance of the 20th century the Wellington Hospital complex was expanded, demolished, added to and re-designed as the need arose, either perceived or urgently required. The entrance was moved from Hospital Road to Riddiford Street, the main thoroughfare through Newtown, and the gates that once marked the entrance-way to Toxwards hospital were moved to the entrance of the city Botanical Gardens where they remain to this day. In 1928 a new administration block and entrance was opened on Riddiford Street which was to serve the people of Wellington for the next 80-odd years. Other buildings were replaced or newly constructed behind this facade to provide facilities, services and treatment for an ever expanding population, and to meet an ever increasing need. As with any public health system, funding has always been an issue and various Governments over the years have considered ideas of consolidation, centralisation, user pays and off-shore treatment. Surviving so many ideas, the bricks and mortar of Wellington Hospital remain as do the many other similar institutions up and down the country, along with the dedicated and care-minded staff who man them. It is important that the citizens of any nation have access to a health system that is the finest which their country can provide. It is the people who make a country and it is the people whose health, welfare and well-being must be provided for by their Government as, after all, a country comprises its citizens and nothing else. For the sake of Wellington Hospital the legacy of Doctor John Patrick Fitzgerald may be traced in a direct and un-broken line from 1840 to 2009 and to the new hospital which Wellington enjoys today. Were it not for visionaries and agitators (and I use the term with the greatest of respect) such as Fitzgerald I doubt if we would have been quite so far advanced in providing care for our citizens over the centuries. And what of our young Amos Burr, probably the first hospital patient in those far-off days of 1840? Despite the loss of his arms, a debility which many of us would mark as the end of our useful lives, Amos lived a quiet but busy existence passing away on May 19th, 1906, at the good age of 84 years. He never sought the limelight for any reason, not even to have his picture taken, and at his own instigation had strap-on wooden forearms made which could be fitted to his stumps. Into these he could screw steel hooks, a knife, a fork & spoon attachment, and other implements. Indeed, he became so skilled in the use of these utensils that there were few things a whole-bodied man could do which were beyond him. On October 10th, 1855, Amos married Lydia Harris Hoskins who had arrived in Nelson on July 11th, 1850, aboard the ship Poictiers. Amos & Lydia had 12 children, one of whom was unfortunately stillborn. Their descendants live on in New Zealand rightly proud as they should be of the brave young man who established the Burr dynasty. © Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |