|

Zeitblick

/ Das Online-Magazin der HillAc -

1. Februar 2010 - Nr. 36

|

City,

My City |

Series 4, Part 7 Even In This Eden All that we know who lie in gaol This story is dedicated to those settlers who, having fallen foul of the law, found themselves on the wrong side of prison bars somewhere in New Zealand. Some of you we know, most of you we don't. As a young and developing country, New Zealand was a magnet for many reasons; its fresh opportunity, its temperate climate and its isolation from the old world. As such the country attracted many of those who sought to make their fortune, to find freedom, to begin a new life or, for some reason, to escape an old one. Some were individuals who, in their late teens or early 20's came out on their own and, not having peer, community or parental guidance slipped into a life of crime. Some of these travelled under assumed names or adopted fictitious identities, intent not on changing old habits but on continuing living off the spoils of larceny, fraud and the hard-earned profits of others. In addition the native tribes of New Zealand now found themselves subject to the new laws of the colony, laws which their own beliefs found it hard to accept and under which they were now ultimately to be punished. The terms gaol, jail and prison have been used interchangeably throughout this story, all meaning much the same thing.

As a British colony it is understandable that the law of New Zealand in the early statute books was inherited from that in operation in Britain during the mid 19th century. Also, because New Zealand was initially governed from New South Wales, some of her laws were adaptations of Australian colonial law which, while also a direct transplant of British law, had been somewhat modified to cope with the conditions found in this Australian penal colony. As a consequence, crimes committed under early New Zealand law allowed for punishment such as fines, confinement in stocks, flogging, imprisonment and execution by hanging depending, of course, on the severity of the crime committed. Capital crime was almost always met with capital punishment. A period of imprisonment as a means of punishing those who broke the law was relatively recent at this time. Prior to this, all manner of death sentences, torture, or a number of other unspeakable penalties, were commonly practiced, perhaps more to inflict suffering on the transgressor than to discourage others from committing similar crimes. A prison was merely a secure place in which to detain perpetrators prior to the application of the instrument of justice, whatever that might be. Certainly incarceration in a jail, gaol or prison for a pre-defined period was not common practice until the early 19th century. Prior to this Britain had adopted an alternative to cope with its squalid and overcrowded prisons - "transportation". Almost 240,000 of those who were convicted of crimes in Britain, but who escaped the ultimate penalty, were shipped off to America or, more often, Australia to serve out their sentences. Bad though this might sound, and certainly in some cases might have been, anyone in such a situation would surely have considered "transportation for life" to be much more preferable than temporary confinement in Newgate Prison followed by the sentence "hanged by the neck until dead". While the saying "out of sight out of mind" seems very appropriate here, many convicts, once they had served out the term of their sentence in the colonies, went on to build comfortable lives for themselves and their future families in the new colony of Australia. Indeed Australia, or the "Lucky Country" as it is known by many of its citizens, was built with the sweat, labour and commitment of many of these former convicts.

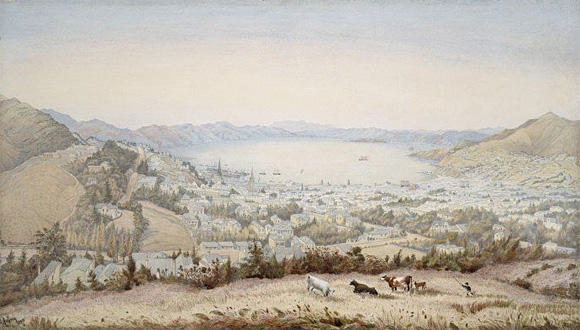

While New Zealand was never a penal colony, and most of its new immigrants were bent on carving out a new life for themselves and their families, some saw the remote location of the colony - on the other side of the world from Britain and Europe - as providing a means of escape and anonymity from the law and its long arm. Although a comparative "Eden" when one equates life in New Zealand with conditions in Britain and Europe at that time, New Zealand's isolation, pioneering wilderness and the very real potential for racial misunderstanding and friction, gave rise to its own unique law and order issues. Prior to colonisation New Zealand had been home to various Maori tribes as well as whalers, sealers, adventurers and the occasional escaped convict from Australia and other penal colonies. From the outset, therefore, there was a need for some form of policing and law enforcement. The New Zealand Company would certainly have had such a contingency in mind and as early as December 1840, barely seven months since the establishment of Wellington, the local newspapers were carrying stories about land being set aside to establish necessary Government facilities such as a Customhouse, a Supreme Court, a Post Office and a Gaol. In 1840 on the arrival of the first immigrants at Petone, on the northern shores of Wellington Harbour, a New Zealand Company hut erected on the beach was appointed as a place of confinement, should it have been necessary. Following the decision to move the township across the harbour to the flat land of Te Aro and Thorndon a "toitoi whare" - a Maori dwelling (whare) built from a form of pampas grass (toitoi) - at Pipitea in Thorndon, was commissioned as the new gaol. This building was reportedly so insecure that the prisoners housed there had to be shackled in irons to prevent them from escaping. Nonetheless some enterprising prisoners did manage to escape by cutting holes in the prison walls large enough to allow them and their shackles to slip through. Many of these prisoners were never seen again and in 1842 this building drew the following comment from William Martin, Chief Justice of New Zealand: "...the common gaol of Wellington was &, I fear, is one of the most wretched of many wretched places which have born that name." Even this blistering criticism wasn't enough to prompt the city to build a new gaol and it wasn't until the following year that the Government, then located at Auckland, decided to allocate funding (estimated at £1,500) for a new, purpose-built, prison to be built at Mount Cook in the Wellington suburb of Te Aro. Plans were prepared by Wellington architect Thomas Fitzgerald in early 1843, created on the newly developed "separate system". This system, a modification of the American model of strict solitary confinement, ensured that prisoners were locked up in individual cells and were only allowed to mingle in the exercise yard, although some versions of this prison design kept them separate even here. The purpose of the British "separate system", developed initially for Pentonville Prison in London, was to destroy the identity of the inmate and to crush the "criminal subculture" which festers within the prison walls. Urgent though the need for a new gaol might have been, the tenders received to build Fitzgerald's design all exceeded the funding available and tenders were thus requested to build a truncated version of the original design. By late 1843 prisoners were moved into the new new gaol, a somewhat smaller version of the original design. One must feel for the tribulations of Henry St Hill, the appointed Sheriff of Wellington at the time, who was duty bound to see the new gaol built but to the severe design of the "separate system" whilst remaining inside a specified budget. The result, while better than the simple hut of former times, would be far from the outcome the people of Wellington had imagined.

Then came October 1848 when the ground shook and many of Wellington's brick buildings, amongst others, were thrown to the ground or so badly damaged that they were uninhabitable. And what had the city fathers constructed our new gaol from, but brick. Newspaper reports of the day made reference in detail to the damage that many buildings had sustained and in passing made reference to the five year old gaol as follows: "The walls of the gaol also, and of a large building at Thorndon, used as a Barrack for soldiers, are so much cracked as to be no longer habitable." The official earthquake report of the day was more detailed when, near the end of a long list of damaged buildings it mentioned that the "Colonial Government Gaol, Two storied brick building, 18in walls, boundary wall 9ft high" had sustained the following damage; "N and S gables thrown out, walls cracked in both stories, side walls cracked." Wellington desperately needed another gaol but, with what appeared to be the same ponderous pace that many governments move forward, it was to be four years later in 1852 before the replacement gaol was completed. Built on a hill overlooking the city, at the southern end of "The Terrace" (then "Woolcombe Street") the building was far enough away from the city to be out of mind and, behind a screen of tall trees, almost out of sight. One must admire the terrific view granted prisoners from this hilltop location and wonder indeed if they appreciated it and if it made their incarceration more bearable. The New Zealand Spectator and Cooks Strait Guardian of April 3rd 1852 gave the following appreciation of the new building prior to the commencement of construction: "Preparations are making for building the new gaol by Mr. Wilson, the contractor, whose tender for the works has been accepted. Two town acres at the end of Wellington-terrace, Te Aro, have been purchased by the Government as the site of the building, which will be one story in height, with a frontage of 165 feet 6in, and a depth in the wings of 82 feet. The building will be of stone, and contains on the south side the principal entrance, a debtor's ward, infirmary, with rooms for the gaoler and his assistants, and the necessary offices, and on the other, or north side, eighteen separate cells for the prisoners, and persons charged with criminal offences, arranged on either side a corridor eight feet wide. The rooms are all ten feet in height, and due care has been taken to provide for proper ventilation. The principal front towards Te Aro has a simple and massive appearance suited to the character of the building, and the whole design, which is by Mr. Roberts, the Government architect, appears to be well adapted to the objects for which it is intended. Suitable provision will be made in the construction of the building for the safe custody of the prisoners, and every possible precaution adopted to provide against any injury arising from earthquakes."

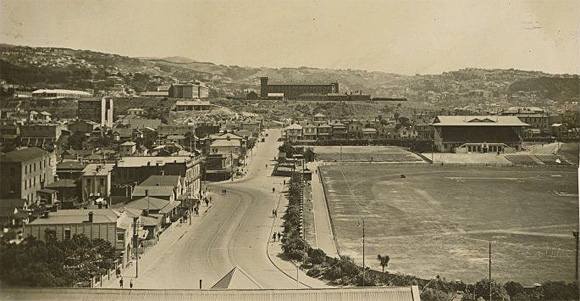

Finally Wellington City had a secure, purpose-built gaol, ideally situated and ideally suited to provide detention services to the city for many years to come. Even after Wellington was chosen as the new Capital in 1865, the prison was well able to cope with the increase in its population and the resulting increase in crime and punishment. That is until the arrival of Arthur Hume from England in 1880. Hume, who had been appointed the new "Inspector-General of Prisons" for New Zealand, had extremely fixed ideas on prison discipline and the rights of prisoners, ideas he had embraced from the chairman of the English Prison Commission, Edmund du Cane. du Cane was well known in England for his extreme ideas on the treatment of prisoners, ideas which included reductions in prisoner education to basic reading and writing, bans on smoking within the prison and reductions in inmate rations. Hume's own beliefs in prison accommodation embraced the now widely disliked "separate system" and one of his first moves was to order the construction of new gaols, based on this design to deal with seasoned offenders, in Auckland, Wellington and Dunedin with the proposed Wellington gaol more strictly adhering to the "separate system" design than any of the others. Thus in 1882, atop the truncated rise of Mount Cook, was erected the rather forbidding and ugly Mount Cook Gaol. It was initially intended to be the "primary penal institution for New Zealand" but continued controversy over its design and construction, and growing opposition from local residents, who did not want this brick monstrosity in their back yards, forced its closure in 1900. The gaol was converted into a military barracks (Alexandra Barracks) and finally demolished in 1929. Adding to the buried history of the city, the only part remaining of this former gaol today is the foundation on which the Dominion Museum was built, now one of the Wellington campuses of Massey University. With the demise of its competitor and possible replacement across the valley, the Terrace Gaol continued to serve Wellington city extremely well for the next 20-odd years. One well known Governor of the gaol during the late 19th century was Mr J P Garvey. Born and educated in Ireland, Garvey gained valuable skills and experience as a member of the Royal Irish Constabulary Force before emigrating to New Zealand in 1874. Arriving in Canterbury, Garvey was appointed as the clerk at the Canterbury Prison before moving into the field of prison discipline. In 1882 he became Chief Warder-in-Charge of the new Mount Cook Gaol after which he was appointed as successor to the Governor of the Terrace Gaol, Micaiah Reid, on his retirement. It was not long before Garvey made his mark on the gaol, the staff, the inmates and on the city as a whole. Never one to be fooled by the "blarney" (after all he grew up in its homeland), Garvey was always fair but let all know that he had a duty to uphold and this was his prime concern. The gaol soon became known by the ironic nickname of "Hotel de Garvey", not because of the ease of life there, but because when you were in the lock-up you were under the rules established by its Governor and only those rules. In a recorded conversation between Mr Garvey and a prisoner we learn a little of his nature "Mr Garvey told me that he did not regard me as the general class of fellows who came under his care, and would do all he could to reduce the discomforts of gaol life. 'But', said he, 'there are always two sides to these questions, and of course I must carry out the regulations.'" In this simple statement, Garvey had set the boundaries by which his rules would apply and, of course, in any other situation his rules would still apply, one assumes rather strictly.

The early 20th century again saw the need for a new building and an increase in space. The Terrace Gaol had served the city well until the early 1920s, some 70 years since it had been built, but a steady increase in population brought an increase in the city's miscreant minority and a consequent increase in the need for prison capacity. A new gaol was built in 1927 on Mount Crawford towards the end of the Miramar Peninsular. Located on a rise above the city, this site again had the potential to afford the prisoners a spectacular view of Wellington and its harbour, a view they may have found captivating had they not been behind bars and a high outer wall. The facility, formerly known as "Mount Crawford Gaol", but now named "Wellington Prison", caters for a portion of the male prison population of the greater Wellington region and has capacity for 120 inmates in minimum and medium security categories. At one time "Wellington Prison" closed when "Rimutaka Prison" in Upper Hutt, formerly known as "Wi Tako Prison" which opened in 1967, was expanded. Although "Rimutaka Prison", New Zealand's largest with capacity for 1,030 low and high risk inmates was initially assessed as being large enough to cope with the regions requirements. "Wellington Prison" has been recently re-opened to deal with issues of prison capacity and prisoner numbers. Female prisoners in the Wellington region are catered for at "Arohata Women's Prison" in the north Wellington suburb of Tawa. While the presence of this facility might draw objection from some residents, its location is discrete enough to be unnoticed by all but those who know what to look for or who know that it is there.

One cannot leave a discussion of the New Zealand penal system without some comment on the supreme penalty - death. The death penalty for murder was abolished in New Zealand in 1961 and for the crime of treason in 1989. In all, 85 people were executed in New Zealand in the 115 years between 1842 and 1957, all by hanging. The first was a young Maori man by the name of Wiremu Kingi Maketu who was convicted of murdering the family for whom he worked in the Bay of Islands. Horrific as this murder was (it involved three children) it was compounded by the bungling of Maketu's execution. At the time of his conviction the fledgling town of Auckland had neither gallows nor an executioner and there was a need to hurriedly procure both. At a cost of £32.8 the gallows were erected outside the entrance to Auckland Gaol (hanging was a public event in those days) but an executioner was not so easy to come by. The first volunteer withdrew his services at the last moment but a replacement was soon found who, for the right price, was willing to undertake the terrible deed. In volunteering to undertake this duty, the new executioner insisted that the hangman's gratuity of £10 be increased to £15.5 payable in advance. The Auckland sheriff, James Coates, had no choice but to agree and was left to pay the extra out of his own pocket. The last person to suffer the ultimate penalty in New Zealand was Walter James Bolton, a farmer from Wanganui, who was convicted of poisoning his wife in 1957. Following his death questions were raised as to the certainty of his guilt and recent years have seen evidence come to light which would seriously question the verdict of the jury. As a key milestone in the development of the New Zealand judicial system, the death of Walter James Bolton has lead us to seek more humane methods of punishing those who break the law, inhumane though many of their crimes might be. © Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |