|

Zeitblick

/ Das Online-Magazin der HillAc -

29. Juni 2010 - Nr. 37

|

City,

My City |

Series 4, Part 8 Spying on the Stars Put three grains of sand Sir James Hopwood Jeans, English Astronomer This story is dedicated to all those who have talked to me about their work. I have met or talked to so many of you over the years:- sailors who crewed the famous sailing ship Pamir; seamen who braved the frigid dangers of the Arctic Circle during World War Two or sailed with the Atlantic Convoys to Britain; harbour police who patrol the waters of Wellington Harbour and beyond; researchers and others who dig beneath the city, uncovering its history and its treasures; those in the Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library and Archives New Zealand whose role it is to preserve this heritage and, more recently, the enthusiastic and dedicated staff of Wellington's Carter Observatory. These and more are the people I have had the pleasure of learning from over the years while researching and writing my stories about Wellington, the stories I call "City, My City". My sincere thanks to Betty Moss, Bob Howard, Dave "Tex" Houston, Chris King, Ian Dimock, Briony Coote, Dawn Muir, Gordon Hudson, Malcolm Macgregor, Charles Smith & his team and to so many more of you to whom I apologise if I have omitted to mention your name. Above all, however, I would like to dedicate this story to Jesper Sorensen of Hamburg, Germany, publisher of this website - "Zeitblick" (Time Perspective). Through the medium of "Zeitblick" I have had the opportunity to do what I have always aspired to do - write. Not only write but to write about the history of my home, New Zealand. Jesper - Dank für alles.

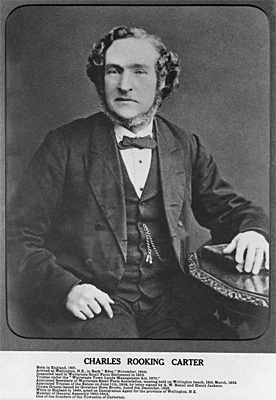

It was almost 11 years since the colony of Wellington had been founded and the morning of November 28th, 1850, dawned bright and clear. The weather on this early summers day was cooler and a little damper than it had been in previous years, but then 1850 was a year of cooler temperatures generally. Some time after dawn the 600 ton New Zealand Company barque "Eden" nosed her way though Wellington Heads and into the harbour proper. "Eden" arrived after a protracted voyage of almost 6 months from London and, despite efforts made by those on board to make her look presentable for her arrival, it was obvious that she was weather-worn and weary. So too was her crew and the passengers on board, mostly new immigrants to the colony, although some were returning after a brief sojourn in Britain, the Home Country. The voyage from the other side of the world, with 133 passengers and cargo for various New Zealand merchants, had been a long one. After first calling at New Plymouth and then Nelson to land immigrants and cargo, the "Eden" proceeded to Wellington from where she would continue south to Dunedin before returning to London via Cape Horn. In the 1850's it was common for New Zealand bound immigrant vessels to touch at several ports on their arrival here rather than one specific port as was later the case during the Vogel period of assisted immigration in the 1870's. Among the few passengers to disembark at Wellington were Charles Rooking Carter and his wife Jane, only too happy, no doubt, to finally arrive in their new home of Wellington. Carter is listed in official New Zealand Company records as a "Labourer" but he had much more to offer his new home than the strength of his back and the sweat of his brow.

Born in the Cumbrian town of Kendal, known locally as "Auld Grey Town" because of the grey slate from which many of its buildings were constructed and more widely for it's "Kendal Mint Cake", Charles was inspired at an early age by the South Pacific voyages of James Cook. At the age of 15 Carter was orphaned following the death of his father and apprenticed himself into the building trade showing at an early age the personality traits of resourcefulness, self-reliance and adaptability which would see him through the next 60 years. While still living in England Carter had become interested in politics and the lifestyle of the working man, writing a series of letters to a local newspaper about the conditions of the working class in Britain. His fascination with New Zealand was evident in many of these letters which sought to show how much better-off ordinary working folk could be by emigrating to New Zealand. On his arrival in Wellington Carter set himself up as a builder and became involved in the consciousness of the new colony, contributing to its cultural, political and business life. He was instrumental in the establishment of the first Building Society in Wellington (the prototype for which had been developed in Birmingham, England, in 1774), sat on the Earthquake Commission following the massive 1855 earthquake and, having purchased a farm in the Wairarapa, represented that district on both the Provincial Council and General Assembly. In 1863 Carter retired from politics and he and his wife returned to England, although he continued his association with Wellington by acting as emigration agent for the province. While back in the "Home Country" Charles and his wife spent much of their time travelling through Europe where he developed a fascination with astronomy, having visited a museum dedicated to Galileo in Florence which he described as "...small but magnificent..." and as containing the "...principle instruments with which he made his scientific discoveries - including his telescope." Carter had a natural regard for his surroundings and for the environment he found himself in, wherever in the world that might be. His experience, therefore, of the great earthquake of 1855, caused him to speak out about the importance of having professional seismologists in a country prone to as many earthquakes as New Zealand and of scientists to help with geological surveys and in charting of the country. He understood, too, the value of astronomical observation to a developing nation, particularly one as remote as New Zealand. While Carter was neither astronomer nor scientist he could appreciate the importance those skills would make to his adopted country and would have been delighted at the appointment of James Hector (later Sir James Hector), respected geologist, scientist and explorer, to head the geologic survey of the Province of Otago. Carter probably knew James Hector well as James moved to Wellington in 1865 and he and Carter would have moved in the same circles. Charles Rooking Carter had done much for the district and people of the Wairarapa and such was the esteem in which residents of the district held him that they petitioned the Government to name a local town after him - hence, on July 26th 1859, the township of Carterton was officially recognised and remains a thriving rural township to this day.

Following the death of his wife, Jane, in September 1895, Charles moved back to Wellington where, on July 22nd 1896, he too passed away at the age of 74. Even in death Charles Rooking Carter was not done with the country of his adoption, nor with Wellington or the Wairarapa. His influence lives on in those places from the Carter Observatory in Wellington and the land he was responsible for reclaiming from Wellington Harbour on which part of Wellington is built, to the town of Carterton in the Wairarapa (including donations of books to its local library) and even a massive Australian Bluegum tree in the churchyard of St Luke's Church, Greytown. The seedling which gave rise to this giant blue gum was one of a dozen Carter had imported from Australia to plant on his property in the Wairarapa. Three of the seedlings went missing on the journey from Wellington and turned up at various places in Greytown which is south of Carterton and on the route from Wellington. At 40 meters tall and 157 years old, the tree at St Luke's is the only one of those three lost seedlings to survive and is perhaps one of the most impressive examples of arboreal splendour to be seen anywhere in New Zealand. One of the most important things that Charles Rooking Carter left to New Zealand was indicated by this passage from his will - "...my trustees shall transfer the same to the Governors for the time being of the New Zealand Institute at Wellington, to form the nucleus of a fund for the erection in or near Wellington aforesaid, and the endowment of a professor and staff, of an Astronomic Observatory fitted with telescope and other suitable instruments for the public use and benefit of the colony, and in the hope that such fund may be augmented by gifts from private donors, and that the Observatory may be subsidised by the Colonial Government and without imposing any duty or obligation in regard thereto, I would indicate my wish that the telescope may be obtained from the factory of Sir H Grubb, in Dublin, Ireland." Carter was correct that the £2,240 he gifted to the city of Wellington for the observatory was not enough to erect an observatory staffed and outfitted for the purpose for which he intended it. It was necessary, therefore, that the New Zealand Institute (from 1933 known as the Royal Society of New Zealand) invested the money to grow the core amount and ensure that an observatory, when built, would be freehold and fully owned by the people of Wellington. The Evening Post of October 5th 1905 reported the closing speech of Dr Richard Cockburn Maclaurin, following his lecture on "Comets", as follows: "Wellington should be equipped with a national observatory and a really good municipal telescope for the study of astronomy. Wellington, he added, was far behind other towns in this respect, although it had, in the Carter bequest, the nucleus of a fund for the advancement of astronomical science." The Evening Post two years later gave an idea of the financial position of Carters bequest from the annual meeting of the New Zealand Institute- "The amount standing to the credit of the Carter bequest on the 31st of December 1906, was £2,504 6s 3d. In addition there is a quantity of scrip in the New Zealand Loan and Mercantile Company at face value. The money is invested by the Public Trustee, and is earning interest at the rate of 4 per centum per annum. The fund represents a bequest by the late C R Carter to the New Zealand Institute for the purpose of establishing an Astronomical Observatory." "The balance sheet for the year just ended showed a credit of £344 14s 8d." This amount brought the total collected for the year ending 1905 to £2,849 0s 11d.

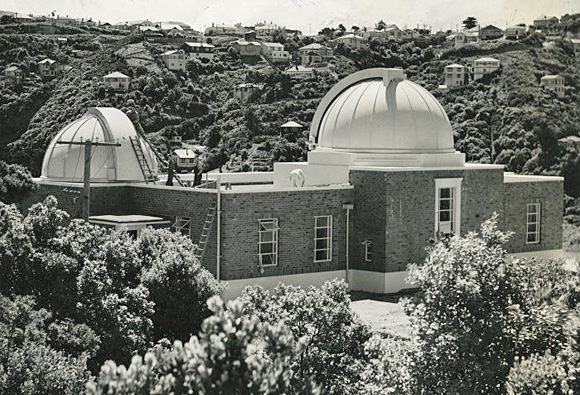

It was to be a long 44 years before the money willed by Carter (known as the Carter Bequest), added to by public donation and driven by the appropriate political conditions, was sufficient to build the establishment known today as the Carter Observatory. 1938 saw Parliament sanction the Carter Observatory Act and in the following year the first Carter Observatory Board was established. The governments position on the bill was supported at the time by two prominent international astronomers; Sir Harold Spencer Jones, Astronomer Royal at Greenwich, said in support of the bill "The proposed scheme, if approved, should prove very fruitful in contributions to astronomical knowledge." and Dr Walter Sydney Adams, Director of the Mount Wilson Observatory in Pasadena, stated "I can think of no expenditure of an equal amount which could be made in a more efficient and effective way." The Carter Observatory Act became one of New Zealand's centennial projects for it had been a scant 100 years since New Zealand, as a British colony, was founded. The Government was determined to take New Zealand's centenary celebrations seriously because "1940 marked not only the centenary of private effort or enterprise but of organised Government in New Zealand." There was a desire to ensure that our centennial celebrations were observed from a "...national point of view..." as the belief was that no other country could show such an extraordinary record of progress in 100 year as New Zealand had done. True or not this was the way we felt in 1940, a country with promise, potential and opportunity. A country which would grow in coming decades and a country which would continually punch above its weight, involving itself in world sport, world politics, world science and world conflict. Neither were the cities and provinces denied the right to recognise their contribution to this 100 years of progress by staging their own celebrations. Wellington, a key player in these celebrations, had special reason to mark 1940 as its own celebration of 100th years of existence coincided with the time frame of the anniversary - November 1939 through May 1940. Anniversary celebrations of significance, among other things, included the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition built on 22 hectares of land near the present Wellington International Airport and the construction of the Centennial Highway between Ngauranga, near Wellington, and Paekakariki which, although opened in November 1938 was branded a centennial project. Into this pageant celebrating New Zealand's progress, pioneering spirit and sense of place in the world the Carter Observatory was born. The Carter Observatory Act transferred land in the Botanical Gardens to the Carter Observatory Board in addition to a historic 9 inch (23 cm) refracting telescope, the Cooke Refractor, shipped to New Zealand in 1905 and installed in the Carter Observatory when it was opened in 1941. The Cooke Refractor remains in the observatory to this day, one of its two treasured historical telescopes.

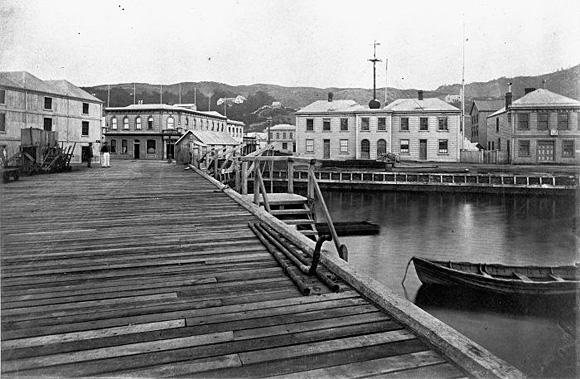

Star gazing has long been important to New Zealand. This is because anyone seeking these remote islands, surrounded as they are by vast tracts of ocean, would have had to understand and be able to read the stellar highways reflected in the cosmos. From ancient Maori and those who preceded them, to explorers such as Able Tasman and James Cook, from the whalers and sealers who sought the riches of the South Pacific, to the first tentative colonial voyagers from Europe and the later mass emigration on sailing ships, spending 3 to 4 months at sea; all needed a knowledge of the heavens to tell time and to chart their way. Some of Wellington's earlier observatories were built to record accurate time, crucial in a country such as New Zealand whose development of and reliance on shipping necessitated standard time keeping. The first time-keeping observatory was built on Wellington's waterfront in 1863 and replaced in 1868 by the Colonial Time-Service Observatory otherwise known as the Colonial Observatory or the Custom House Observatory. This housed a "time ball" (see image below) which, to record time for ships in the harbour and other observers within sight, was hoisted to the top of its mast and dropped at precisely 12 noon. All key ports in New Zealand had such an apparatus and, where a telescope was also used, this was solely for time-keeping rather than any astronomical purpose. In 1869, due to the encroachment of the city and the growth of trees surrounding the waterfront, it was decided to move the Colonial Observatory to a site considered "the best in Wellington...for quiet security of never having the meridian posts hidden". Tenders to erect the building were advertised in March 1869 and the new Colonial Observatory was completed later that year. The death of Richard John Seddon in 1905, Prime Minister of New Zealand for 13 years, necessitated the demolition of the Colonial Observatory to make way for his tomb. Never let it be said, however, that politics should stand in the way of science and a new observatory was built two years later, high above the city, near the Kelburn end of the Cable Car. Originally named the Hector Observatory after the gentleman considered by most to be the founder of New Zealand scientific research, its name was changed in 1925 to the Dominion Observatory. Although the primary function of the observatory was time-keeping, meteorology and climatology, seismology was added to its list of responsibilities and some astronomical observations were also permitted. In 1917 Wellington's first genuine astronomical observatory was opened on a low rise above and in front of the present day Carter Observatory. Named for Thomas King a member of the Royal Astronomical Society, the Philosophical Society and Astronomical Observer for New Zealand between 1887 and 1911, the observatory was the first public observatory in Wellington where citizens could observe major astronomical events such as the apparition of Halley's Comet in May 1910. While initial public attendance was poor, major astronomical events such as the Earth's close proximity to Mars in August 1924, served to make the observatory popular and it became the headquarters of the Wellington Astronomical Society. A period of neglect between the establishment of Carter and 1995 saw the building fall into disrepair but it has since been refurbished and remains the headquarters of the Wellington Astronomical Society under the control of the Carter Observatory with pride of place being given to the 128 year old, 12.5cm Grubb telescope built in Ireland in 1882. Before The Carter came into being a 4th observatory was constructed in Wellington in 1924. Built of corrugated iron it was named "The Tin Shed", it housed a 23cm telescope obtained from the Marist Brothers Seminary in Napier, and met its end when it was demolished to make way for the construction of the Carter Observatory.

Throughout its 70 years of history the Carter Observatory has undergone 3 significant renovations. In the 1960's alterations and improvements were made possible by the Ruth Crisp Bequest, a sum of money donated to The Carter from the estate of New Zealand author and philanthropist Ruth Crisp. This bequest allowed for the expansion of the building and the construction of a two-storey library and office wing. In addition a third telescope was purchased, a 41cm Boller & Chivens reflecting telescope made in the United States. Known as the "Ruth Crisp Telescope", it was installed in Carters second dome. 1991 saw the relocation of the "Golden Bay Planetarium" from downtown Wellington and its incorporation into the Carter Observatory building where it became the observatories foyer, visitor centre and theatre. More recently in 2006 the Carter Observatory Board, with $2.2 million of funding provided by the Wellington City Council, commenced a complete overhaul observatory including the visitor centre and planetarium. The intention of this refurbishment was to turn Carter Observatory into a modern, world class, astronomical tourist attraction and education centre capable of hosting local residents, national visitors and international tourists alike. In this challenge those involved have succeeded admirably providing an excellent, modern educational facility and learning environment. Here one can lose themselves in displays and interactive, hands-on, exhibitions on a wide range of astronomical subjects. Here one can gain a broad knowledge of ancient Maori and Pacific Island navigational and astronomical lore, receive a comprehensive view of the skies over the Southern Hemisphere and the universe beyond and learn of New Zealand's place in the past, present and future dimensions of astronomical science as well as learning about what New Zealand has given to this branch of the sciences, an overall a learning experience which is without equal anywhere in New Zealand.

The Carter Observatory building is not the only one on this rise above Wellington's Botanical Gardens and the area is something of a historic precinct to Wellington's astronomical and scientific past. Above the Carter Observatory is the Thomas King Observatory, originally known as the King Edward VII Observatory, which was built in 1912. Popular in the 1920's and 30's in more recent years the building fell into disrepair. Under the care of The Carter, the building was renovated in 1996 it is now used for public astronomy and education purposes and is used today by the Wellington Astronomical Society as its headquarters and base for operations. Beneath the King Observatory and partially shown on the right of the picture below is the small dome which once housed an astrolabe - an instrument used to measure the altitude of stars and planets. The astrolabe, one of three in the world and still carefully stored in "Gordon's Grotto", was used during the International Geophysical Year of 1857 to 1858 to measure the wobbling of the earth on it's axis. As a by-product of this study the centre of this dome is more accurately known than any other geographical point in New Zealand. Showing in the middle of this picture is the Dominion Observatory, built in 1907 as the Hector Observatory to measure time as part of New Zealand's Colonial Time Service. The octagonal room on the roof, built to the same pattern as that of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich was used to house the astronomical clocks. Daily from here a time signal was sent to the Wellington Telegraph Office from where it was relayed to post offices, ports and railway stations around the country. To the front of the Dominion Observatory is a German-built Krupp field artillery gun, captured in 1917 during World War One. The gun has been displayed in various places around Wellington and in its present location marks the location of "Botanic Garden Battery" between 1894 and 1904. The battery, along with others surrounding Wellington Harbour, was constructed in response to what was then called "The Russian Scare". The raised platform behind the Krupp gun indicates the location of the former underground ammunition battery, which, was built to service the gun. In behind the Krupp gun and the Dominion Observatory may be seen the headquarters of the New Zealand Meteorological Service known as the MetService. To the left and around the side of the Carter Observatory is an unusual sundial called "The Sundial of Human Involvement". It was constructed with funding from the Charles Plimmer Bequest to mark the arrival of John Plimmer, famed for Plimmer's Ark on the Wellington waterfront, in 1841. The Plimmer family has been associated with Wellington for more than 150 years. By standing on the date of a year with ones back to the sun the resulting shadow will tell local standard time.

© Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |