Zeitblick

- Series A HillAc Production |

| City,

My City - Series Two By Peter Wells Part 4 The Russian Convoys This story is dedicated to all those sailors whose courage in the face of overwhelming odds helped supply the needs of the Soviet Union during World War Two, in particular Christopher King, (Royal Navy) and the late Hunter "Mick" Ryan MacAskill (Merchant Navy).

|

|

|

On February 22nd 1847 my Great Grandfather, Thomas Leys Hadden Dennison, was born in the middle of the Arctic Ocean. His father was a ship owner and traded between Aberdeen and Archangel in Northern Russia. Born on the sea, born to the sea of a seafaring family and eventually to become a seaman himself, Hadden Dennison as he was known arrived in New Zealand as Purser on board the immigrant sailing ship 'Wild Deer". Little did he or anyone know at the time, that almost 100 years after he was born, another generation of seamen from the Commonwealth and allied nations, including his adopted country of New Zealand, would battle those storm-tossed freezing Arctic seas to maintain a vital supply line between Soviet Russia and its Western confederates who had become not so much allies as opponents of the same enemy. Prior to the outbreak of World War II Hitler had entered into a non-aggression pact with Stalin. Unknown to Stalin, however, this pact was calculated to hold the Russian armies at bay whilst the Wehrmacht, having torn Western Poland apart, swept through the Low Countries towards the English Channel and Britain in an advance which was terminated in the west by the courageous efforts of the pilots of Britain's Royal Air Force. Unable to defeat that small island nation off the coast of Europe, Hitler turned the awesome might of his armed forces eastward toward the Soviet Union in an attempt to enslave or eliminate its Slavic population whom he despised. Russia possessed a wealth of raw materials and it was these raw materials plus the living space ("Lebensraum") for an expanding German population that were the goals of this invasion. In one of the most spectacular military bloopers of all time, Hitler moved the bulk of his armed forces to the east (thus relieving the pressure on Britain) and, on June 22nd 1941, launched Operation Barbarossa, an all-out attack on the Soviet Union. This attack took the Russian armed forces almost completely by surprise although numerous warnings had been received over previous months and Russia now found itself fighting a common adversary alongside England, which had until recently been its enemy. At war against a huge and well-equipped German army, the Soviet Union needed supplies, and needed them quickly. Arms and munitions; food and raw materials; tanks and vehicles; planes and the skills to fly them; fuel oil and gasoline and just about everything one could think of. There was almost nothing that Stalinist Russia didn't need, in great quantities and in even greater urgency. From this urgency, and through the determination and courage of the sailors manning the cargo ships and naval escorts of the western allies, the Russian Convoys were born. Fending off extravagant Soviet demands and in a desperate bid to keep Russia in the war, Winston Churchill committed his nation, in part through the generous Lend-Lease scheme set up between Britain and the still neutral United States, to the establishment of a sea-based lifeline into Russia. From the end of September 1941 through until late May 1945, 78 convoys were to grind their way north and east through the coldly inhospitable storm tossed Arctic Ocean towards North Russia. The use of convoys for the allies was to become so successful that German naval commander Admiral Karl Dönitz was reported after the war as saying 'The German submarine campaign was wrecked by the introduction of the convoy system.'

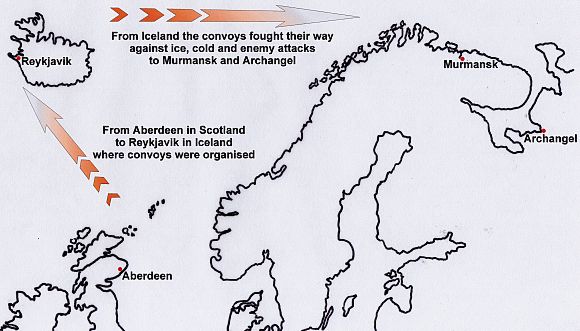

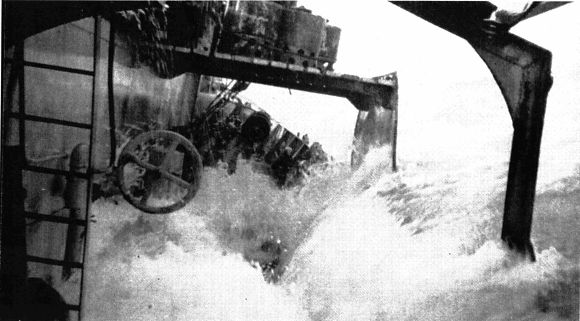

Of all convoy routes of World War II the most dangerous was that followed by ships carrying supplies up into the Norwegian and Barents Seas and on to the North Russian ports of Murmansk and Archangel - convoys which would become famously known as The Russian Convoys. The Norwegian mainland, abreast of which the convoys must sail, was occupied by German forces and bristled with U-Boats, attack aircraft and naval vessels of all types making each convoy a sitting duck. Often, though, the sailors considered the bone-numbing cold and unpredictable storms to be a worse enemy than these German attacks. Chris King, President of the the Russian Convoy Club of New Zealand and a much appreciated source of information for this story, tells us that "it was a shock for all of us. Once you left Iceland and got that rough weather - there's nothing as bad as those seas up there. All this was just part of our ship daily routine. There were also the enemy attacks from the air and sea, and always the dreaded mines often lurking under the water ahead of the convoy. All very frightening but accepted with cursing and swearing but without questions. There was no option, no turning back or running for cover." A Naval Surgeon and Russian convoy veteran once said he felt that fear against an arctic background was far more difficult to control than in some other theatres of war. 'The arctic was cruelly cold and with its dreadful loneliness came the utter hopelessness of survival if the worst should happen'. The Corvette HMS Bluebell, on which Chris King had previously served, was torpedoed and sunk in February 1945 with the loss of 89 of its 90 crew. The one surviving crewman miraculously survived 45 minutes in the icy sea before being pulled to safety. And of course the ice was everywhere. Not just one layer or two but several layers thick. Solidified sea spray thrown up by the ever-restless ocean. Ice made it difficult to walk around the ship and could remove exposed skin from anywhere on the body. Ice built up on the superstructure and could make the ship top-heavy. Ice could freeze the guns, rendering the ship defenceless. A friend of my Mother´s, a veteran of the Russian convoys, once told her that no matter how many layers of clothing you put on you were always cold. Talking of these sub-zero temperatures Chris King relates "Our gear on the upper deck in those freezing conditions would usually be overalls, seaboots, duffel coat and oilskins with a towel tucked in around the neck to keep the water out."

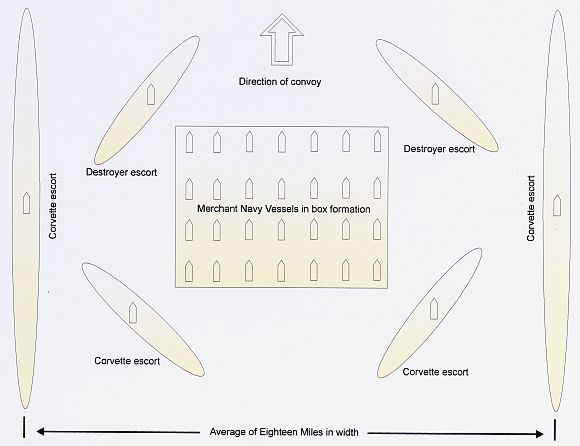

The success of each convoy was varied due to an assortment of conditions and events but the scheduling, planning and set up of them was undertaken with meticulous precision. Each convoy was preceded by a planning meeting attended by key Royal Navy, Merchant Navy and Intelligence personnel as well as some of the convoy captains. On leaving Scotland, the ships headed north west to Iceland where they gathered together in the bitterly cold and exposed Hvalfjordur Fiord near the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik. Merchant vessels from Britain (including New Zealand), America, Holland, Canada, Panama, Belgium, Norway and Russia gathered together, riding low in the water laden with cargoes of supplies destined for the Soviet Union. The convoys adopted the classic box formation (see below), successfully used on the Atlantic convoy runs. Here the merchant vessels were placed strategically within the box depending on their cargo and vulnerability to attack. Those carrying raw materials were placed around the perimeter of the formation whilst those carrying ammunition, fuel and troops were situated in the centre. This whole was surrounded by an escort of constantly moving naval vessels, made up mainly of destroyers and the versatile little corvette. It has been said that the sailors who manned the merchant vessels coolly calculated where they would sleep on board based on the cargo the ship was carrying. If she was carrying iron ore, for instance, one slept on deck as there was only one brief chance to escape a ship that was bound to go straight to the bottom following a torpedo strike. Then again, with a general cargo on board, a sailor slept below decks with clothes on as escape was calculated in minutes. On the other hand, if the ship carried aviation fuel, one was free to sleep naked below decks and behind locked doors as once the torpedo struck it didn't matter.

Whilst serving on vessels in the Arctic, sailors often experienced many of this realms´ proclivities of nature. Apart from the intensity of arctic storms and the savagery of the cold, the annual seasons were something many found difficult to get used to. Being so far north the Arctic Region effectively has only two seasons - Summer and Winter. During the Summer there is constant daylight as the sun never dips below the horizon for a period of about 6 months whilst during winter, and for the same period of time, the sun never rises above the horizon giving rise to a disorienting twilight. In addition a phenomenon sometimes seen elsewhere in the world but perhaps more apparent in the Arctic is Sea Smoke. A form of fog, Sea Smoke occurs when frigid polar air meets the relatively warm, moist air at the water's surface. When looking out over a frigid arctic ocean the sea may give every impression that the surface is smoking, as if on fire, but what one sees are actually plumes of warm air rising from the sea which condense and become visible, much like seeing one´s breath on a cold day.

A significant number of New Zealand sailors, many of whom called Wellington home, served on board both merchant and naval vessels of the Russian Convoys. Since the end of WW II the situation of East vs West world politics, particularly those annoyingly abrasive characteristics of Socialist vs Capitalist ideologies, has meant that for an uncomfortably long period of time these brave sailors both here and in other nations were denied recognition by the Soviet administration, an administration that they fought long and hard to support. In fact it was considered disloyal to the Soviet ideal to even acknowledge the fact that, during WW II, Mother Russia had been aided in her most wretched moment by a capitalist alliance. No Convoy Veteran sought to brag of their exploits, indeed some merely wished to forget, but simple recognition of this period where their lives were risked and some lost and natures extremes were endured, was important to many. There was no glamour, there never is in war, but as the late New Zealand poet Denis Glover said in a typical moment of understatement, "We went where we were sent - and it could be frightening."

By 1975 the Soviet bureaucracy, embarrassed by its own lack of appreciation towards Western veterans, began to relax its attitude and came to recognise the efforts that had been made on its behalf during the dark days of World War Two. However it took still longer before any serious public recognition was afforded Convoy Veterans. By the year 2000 Russian diplomats around the world had begun actively seeking out surviving Convoy Veterans in order to honour them and in the process more than 14,000 medals have since been awarded to Convoy and RAF veterans supporting the Soviet Union during the war. On May 9th 2005, the Russian Embassy in Wellington invited all New Zealand veterans of the Arctic Convoys, potentially up to 300 former sailors, to commemorate the 60th anniversary of Victory Day in Russia (May 8th in Russia but May 9th in the New Zealand). At these celebrations New Zealand's heroes of the Russian Convoys were finally and very publicly honoured with the unveiling of a memorial plaque in Frank Kitts Park. |

|

Logo of the Russian Convoy Club of New Zealand |

To contact the Russian Convoy Club of New Zealand please write to Chris

King |

|

©

Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |

|