Zeitblick

- Series A HillAc Production |

|

City,

My City - Series Two Part 5 Nobu

Shirase "Study

the treasures under the Antarctica

It is the nature of man to seek the undiscovered and strive to achieve the unaccomplished, frequently suffering the greatest personal discomfort, sometimes at the expense of life itself. In 1911, driven to achieve the ultimate Antarctic goal, two explorers, Britain's Sir Robert Falcon Scott and Norway's Roald Amundsen, raced towards the South Pole with the single-minded aim of being the first to arrive and the first to mark the event for their respective nations. Unknown to both, and to many others in the world, both then and now, a third competitor in the race was not far behind and indeed was close enough to cross the path of Roald Amundsen, who was the eventual winner of the great southern dash. This "third competitor" was Nobu Shirase, a Japanese adventurer, self-styled explorer and former Lieutenant in the Japanese Army who had sought adventure from a very early age. Born in 1861 in the village of Konoura, north-western Honshu, to a Buddhist monk of Jorenji Temple, Shirase's boyhood imagination became immersed in the stories he heard of adventurers and explorers, particularly those who were challenged by the Arctic wastes to the north. It is said that at 11 years of age, after listening to a story from his teacher about the North Pole, Shirase resolved, if only to himself, that he would one day lead an expedition of discovery. On leaving school in 1879 he entered the school for Buddhist priests at Sensoji Temple in Asakusa, Tokyo Prefecture. Soon deciding, however, that he could not mix the life of a Buddhist priest with that of an adventurer he quit and entered the army school for non-commissioned officers.

Four years later, in 1883, Shirase was able to realise his dream of exploration when he joined the naval squad who accompanied an expedition to explore the Chishima Island chain to the north of Hokkaido. Stretched like a silken rope joining north eastern Hokkaido and the Kamchatka Peninsula in eastern Siberia, the Chishima Islands, as they were known before 1945, had been a hotbed of claim and counter claim throughout the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries by both Japan and Russia but were at that time in Japanese possession. (1) Part of the group landed on the northeastern island of Senshu in June 1883 to commence preparations, however very poor planning of the expedition led to the deaths of ten of its members on two nearby islands and on June 28th the leader, Naritada Gunji, left Senshu island. Shirase, however, remained there over the winter along with five further members who had arrived to take over exploration duties. During the second winter period, three of this group of six died from scurvy and on August 21st, the survivors were rescued by the Yagumo, a ship dispatched by the Governor of Hokkaido. Unsuccessful though this expedition had been, Shirase had experienced a taste of sub-arctic exploration which was to stand him in good stead for future events.

Planning all the while to be first to the North Pole, Shirase was to have his plans upset when, on April 6th, 1909, the American explorer, Robert E Peary, claimed to have achieved that goal. (2) Not to be put off by a mere formality, Shirase turned his attention 180 degrees to focus on the Antarctic and the yet to be conquered South Pole. Full of enthusiasm, he sought to raise funds for his expedition by initially approaching the Japanese Government. As a nation, however, Japan did not have an expansive tradition of exploration and his request was met with some indifference. Although the Government initially voted him 30,000 Yen, Shirase never in fact received anything. Again not to have his plans overthrown by a minor set back, Shirase turned to public donations to raise the necessary funds and on July 5th, 1910, a public lecture concerning the planned expedition was given to a large crowd in Tokyo. From this the "Antarctic Expedition Supporters' Association" was set up for which Shigenobu Okuma, a former Japanese Premier, was to take up the post of President. In addition, a theatrical portrayal of the expedition and various newspaper campaigns ensured the public became more receptive to the idea and the contributions began to flow in. Although the money raised was not a large amount it was sufficient to get the expedition fitted out and underway and on December 1st 1910 its members left Shibaura, Tokyo on board the Kainan Maru.

On February 7th, 1911 the Kainan Maru reached Wellington, New Zealand and slipped quietly into Wellington Harbour. As would be expected the local newspapers recorded the event. Some, such as the Evening Post, with good will and a touch of unintentional humour while others wrote with pointed hostility and ethnic mis-understanding. The Evening Post of February 8th, 1911 records events thus: Of

the arrival and purpose Of

contact between East and West Of

first impressions Of

their vessel Of

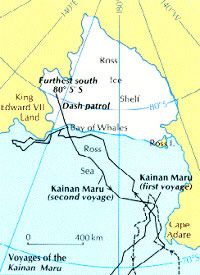

their plans and programme Such are the ambitions of man whose plans, though made with precision, are doomed to be shattered if the weather does not cooperate. Nobu Shirase and his team left Wellington on February 11th after being farewelled by members of the Marine Department, the Government Meteorologist, representatives of the Wellington Harbour Board and the Minister for Internal Affairs. It is not recorded if there was any farewell by members of the public. The Kainan Maru sailed south through icebergs and increasingly cold temperatures, making landfall on March 6th on the coast of Antarctica at Victoria Land. The weather was becoming progressively worse as the ship headed south and when it became impossible to proceed any further Shirase reluctantly ordered his ship to turn and head north to Australia. Arriving in Sydney on May 1st the expedition was greeted with mistrust and hostility but the generosity of a local resident enabled them to set up their prefabricated hut in a garden in the elegant Sydney suburb of Vaucluse on the shores of Sydney Harbour. Captain Nomura and some of the crew returned to Japan to seek further funding, while Shirase and his men lived close to a beggars existence during their time in Australia. The public mistrust remained but the intervention of Professor Edgeworth David, himself a noted Antarctic explorer, did much to allay the feelings of the populace as a whole. The time wasted in Australia must have been exasperating for Shirase as he came to accept that he was now so far behind Scott and Amundsen that any realistic attempt at being the first to the South Pole was pointless. In this light he moderated his plans and when the Kainan Maru sailed south once more it was with the intention of undertaking scientific exploration of King Edward VII Land. On January 16th, 1912 the expedition reached the Ross Ice Shelf, significantly further south than they had been before, and here in the Bay of Whales they were startled to see another vessel which turned out to be Amundsen's ship Fram, waiting for him to return from the Pole. Visits were exchanged with the Norwegian vessel but language difficulties made any serious dialogue impossible. From where the Kainan Maru was moored Shirase and his company faced an almost sheer climb of 90 meters to the top of the ice shelf which they attained after 60 hours of gruelling endeavour. Having achieved this point Shirase became encouraged once more and formed his celebrated "Dash Patrol" in an attempt to race with dog sleds for the South Pole.

In reality their efforts were to become anything but a "Dash" as on the very first day a blizzard forced them to seek shelter after having covered a mere 13 kilometers. Nine days of struggle and 257 kilometers later, on January 28th, Shirase saw the senselessness of any further effort and made the decision to turn back. He and his men lined up before dawn at south latitude 80o 05', the furthest southern point they would achieve, and stood beneath the Japanese flag to salute the Emperor with a traditional Banzai ceremony. Burying a copper receptacle containing a record of their valiant efforts, the "Dash Patrol" returned to the drop-off point and again boarded the Kainan Maru for the long journey home to Japan, stopping off once again at Wellington. Shirase and his team returned home to Shibaura on June 20th, 1912, having undertaken an expedition of some 48,000 kilometers since leaving Japan. It must be noted, too, that this date is a mere one month short of Shirase's planned return date and shows how accurately he was able to plan the whole expedition. Although they had failed to reach the South Pole, as they had set out to do, they certainly managed to achieve all of their stated objectives from the time of their second sailing and were greeted by 50,000 well-wishers, in stark contrast to their departure from Japan which was only witnessed by a handful of students.

When everything was added up, the cost of the expedition was estimated at around 125,000 Yen, significantly more than the 72,000 Yen raised in the days before their departure and Lieutenant Shirase found himself in debt. He managed to sell his ship, the Kainan Maru, for 20,000 Yen but was forced to make up the balance himself, thus spending the rest of his life in continuous travel in an attempt to raise enough money to pay off this debt. Old and alone, Shirase spent his last days in a rented room on the second floor of Suzuki's Fish Shop in the town of Koromo, Aichi Prefecture. At 9:00 am on September 4th, 1946, at the age of 85, a blocked intestine took the life of Lieutenant Nobu Shirase, hero, adventurer and Japans first Antarctic explorer. Little did the nearby residents know that this neighbour, this old man, was the famous explorer of the Antarctic and his funeral was lonely with no one present to offer their sympathy or their respect, although ironically he held the respect of all of Japan. (1) The island chain is presently in Russian possession and known as Kurilskiye Ostrova. (2) This claim has been disputed over the years and even today there are some who doubt it. © Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |