Zeitblick

- Series A HillAc Production |

City,

My City - Series Two Part 8 The Fourth Service, the Merchant Navy This story is dedicated to those wartime sailors without uniforms who fought to keep the lifelines of this country and its allies open ensuring the delivery of vital supplies to the battle fronts of the world.

War invariably has an impact on civilians from all walks of life and in all age ranges. Even those as far removed from the place of battle as the young and old of New Zealand were not immune during World War Two. Since many of the able-bodied men and women of this country had been posted overseas with the New Zealand armed forces it often fell to those too young or too old for military service, or who had skills best utilised in this field, to maintain this country's vital supply and trade lifeline with Britain. The Home Country, 12,000 miles and one hemisphere away, remained the destination of the bulk of our exports and the source of the greater part of our imports and it was the role of the Merchant Marine to ensure that this lifeline was maintained. The onset of war did little to change things, but ensured that the majority of those already serving on cargo ships continued to serve on cargo ships and that any vacancies were filled by civilian volunteers aged between 14 and 75. The difference now was that they had an enemy intent only on sinking them. These men became trained and skilled in their craft as sailors, an art and custom established over centuries of ocean dominance by Britain and passed down, through this country's colonisation, to our local seafarers. Their role was fulfilled, as only merchant sailors were able, with dedication, devotion to duty and hard work. But they were civilians and not soldiers and were often expected to defend their cargo against a fully armed and proficient enemy which they did, very often, without guns and certainly without the rights and privileges of a uniform and any large amount of military training. The feeling at the time was summed up in the words of Dewi Browne quoted from the book "Hell or High Water" - "I can't remember whether we expected it or not. But the point is, a chap's a seaman and you just keep going, war or no war, that's your job."

On August 26th 1939, in anticipation of war, the British Admiralty assumed control of all British merchant vessels. Shortly afterwards, on September 1st 1939, following the invasion of Poland, the New Zealand Government did the same by bringing all shipping in local waters under its control. Two days later, on September 3rd, Britain, France, Australia and New Zealand declared war on Germany thus heralding the beginning of the longest single conflict of the war - the Battle of the Atlantic. Several thousand New Zealanders served in the Merchant Navy during World War Two a task that was vital to the Allied war effort. The Merchant Navy was so highly regarded that it earned the name "The Fourth Service", serving alongside the Army, Air Force and Navy. Food, fuel, raw materials, military equipment, troops and essential supplies were ferried across vast ocean distances by often lightly or completely un-armed vessels manned by civilian sailors of the Merchant Navy. Allied combatants and battlefields around the world including the Pacific theatre and New Zealand troops fighting in North Africa and the Mediterranean were supplied by these sailors and the 12,000 mile lifeline between New Zealand and Britain kept our economy going during those dark days. The Merchant Navy also helped feed our British allies, the New Zealand Government of the day offering its entire exportable surplus of meat, butter, cheese, wool and other agricultural produce to the British war effort. In all, New Zealand sent 2 million tons of meat, 1.3 million tons of butter and cheese, and 4 million bales of wool half way around the world in merchant ships. The Minister of Marketing, Benjamin Roberts, acknowledged at the end of the war, "This has only been accomplished at great hazard and with the loss of many lives and many ships... It is no exaggeration to say that the Merchant Navy has been the axis round which the war effort of the United Nations has revolved."

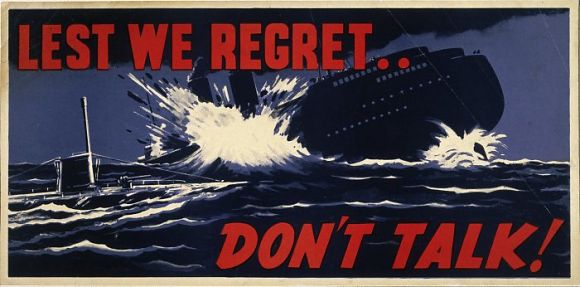

In December 1939 New Zealand's domestic registry listed 186 ships, providing employment for 3000 seafarers. It was these seamen and their vessels which were nationalised by the New Zealand Government to provide a united cargo line to aid the war effort in whatever way was decided. Many of the local vessels had previously been utilised on the "short-sea" routes from New Zealand - trans-Tasman, the South Pacific and various coastal routes around the country. In addition the Union Steam Ship Company, the jewel in New Zealand's maritime crown, became one of the Governments most valuable war assets. The Monowai was converted to an armed merchant cruiser, the Awatea carried troops and evacuees and the old Maunganui was used successfully as a hospital ship carrying upwards of 5600 patients during the war. Other vessels such as the Rangatira, Wahine, Matua and Aorangi all gave outstanding service as troop carriers. Of course there were losses inflicted on the New Zealand merchant fleet. Between June 1940 and the middle of 1941, the German commerce raiders Orion and Komet had an almost free hand throughout the South Pacific and Tasman Sea. By laying mines across the north and eastern approaches to the Hauraki Gulf, outside Auckland, the Orion succeeded in sinking the 13,000 ton RMS Niagara as she set out on her regular run to Canada across the Pacific. The Niagara was the first of many vessels to fall to these warships, others being Rangitane, Vinni, Holmewood, Komata and the gritty little Turakina which, on August 20th 1940, took on the Orion in the Tasman Sea in a one-sided but gutsy battle during which she refused to give up, eventually being sunk with the loss of most of her crew. As vessels began to be attacked and sunk with greater regularity the possibility was raised of information leaks and the possiblility of spies within New Zealand. While this was eventually discounted, it led to more stringent controls on the flow of information and warnings to the public about speaking too openly. The eventual withdrawal of these German vessels from the Pacific relieved the threat to New Zealand shipping, a threat which was never replaced by the Japanese navy who lacked the German enthusiasm for commerce raiding. During this time the Indian Ocean remained a dangerous place but it was in the Atlantic that the greatest threat lay in the path of thousands of allied vessels.

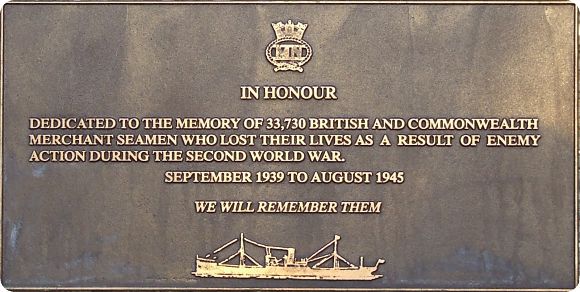

It would seem that a battle fought half a world away might have minimal impact on New Zealand but a German victory would sever the links New Zealand had with Britain, posing a grave threat to New Zealand's economy, freedom and her very existence. It was essential, therefore, that the lifeline across the Atlantic be maintained at all costs and the cost was to be high. The loss of over 33,000 Commonwealth merchant sailors and countless millions of tons of shipping, not to mention the cargo that these vessels carried, was to be the cost of success. In order to help ensure the safety of these vessels and their crew and cargo, the British Admiralty ordered the introduction of the "convoy system" where ships were grouped strategically together with the protection of a naval, and sometimes air force, escort. As he was so often able to do, in April 1941 Winston Churchill pithily expressed in few words the critical nature of the undertaking facing the Allies - "In order to win this war Hitler must either conquer this island by invasion or he must cut the ocean lifeline which joins us to the United States..." The German strategy in the Atlantic was quite simple; to starve Britain into submission by destroying merchant shipping and their contents faster than they could be replaced.

The Battle of the Atlantic lasted for 2,074 days, exactly the duration of the war in Europe. On almost every one of these days allied shipping was lost in the Atlantic with the loss of life and cargo. An understanding of the enormity of equipment and supplies shipped during those 6 years may be gained from the following quote from "Liverpool and the Battle of the Atlantic" by Paul Kemp - "...if all the supplies carried by just one average sized Atlantic convoy (35 ships) were gathered together they would fill a line of ten ton trucks spaced 50 yards apart which would stretch from Inverness to Southampton via Carlisle." Although some New Zealand vessels spent time in the Atlantic, most New Zealand merchant seafarers served under the British flag, affectionately called the "Red Duster". To cut the vital supply lifelines to Britain and the Soviet Union, Germany utilised many of the surface vessels in it naval forces, coupled with long range aircraft such as the Focke Wulf FW 200 Condor, mines and the ubiquitous U-Boat, easily the deadliest adversary faced by the merchant vessels. Had Germany succeeded in its aim of severing this Trans-Atlantic lifeline, Britain would soon have been faced with the two choices of starve or surrender. The vast industrial resources of the United States would no longer be available to Britain and the Soviet Union and the ultimate liberation of Europe would not have been achieved.

The courageous deeds of these civilian seamen and the vital role they played in the Allied war effort cannot be celebrated highly enough. Most were untrained in the arts of war beyond the operation of whatever small armament their ships carried. Indeed many vessels carried no armament at all. No other group of Commonwealth citizens faced such risks against a heavily armed and determined enemy during wartime. Most were not troubled by the principles and strategies behind the war beyond a belief in the "rightness" of what they were fighting to achieve. What drove them was a determination to keep going, to achieve the peace for which the free world fought and to be able, once more, to steam peacefully across the seas with the ships lights on. As with all those who have served New Zealand in uniform, the Merchant Navy truly deserves the tribute "We Will Remember Them". © Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |