|

Zeitblick

/ Das Online-Magazin der HillAc -

21. März 2008 - Nr. 28

|

|

City, My City |

|

|

Series 3, Part 1 Children of Kupe

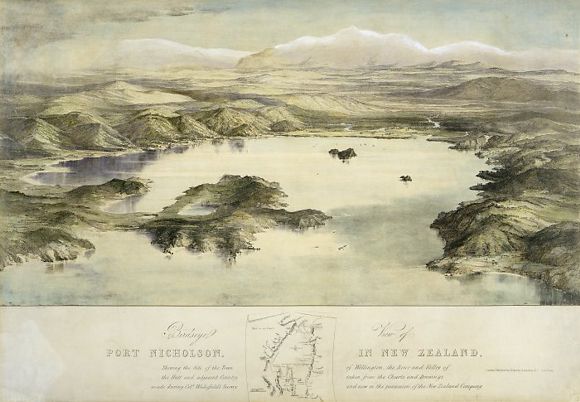

Approximately one and a half million years ago the faultline to the west of Wellington ruptured sending its eastern portion plunging downward and its western flank up to form a long steep ridge - the present day western hills of Wellington. Of the resulting series of basins formed by this upheaval the southern-most, and deepest, was to form the depression that became our present-day Wellington Harbour. Residual high points of land, originally forming the peaks of these now drowned ridges, became the islands of the harbour - respectively from north to south Leper Island (Mokopuna), Somes (Matiu) and Ward (Makoro). In the beginning, however, there were actually four islands in the harbour. The neck of land now known as the Miramar Peninsula was initially detached from the mainland as the island of Motukairangi sitting at the western side of the harbour entrance. An immense earthquake in about 1460 raised the sea floor between Motukairangi Island and the mainland forming a swampy but relatively dry isthmus and completely changing the appearance of the harbour. This isthmus was further raised by the great earthquake of 1855 (magnitude 8) and is now the location, on its eastern boundary, of Wellington International Airport.

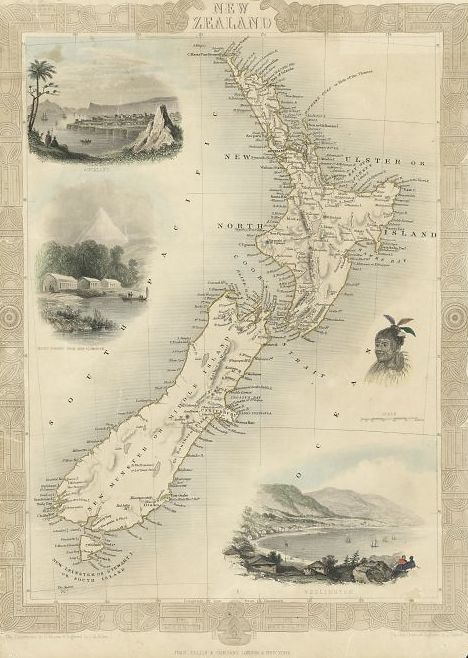

In Maori tradition the North Island of New Zealand - Te Ika-a-Maui or The Fish of Maui - was hauled from the sea by the mythical fisherman Maui and lay flat out with its one visible eye, represented by Lake Wairarapa, gazing skywards. The mouth of this immense marine creature is symbolised by Wellington Harbour, its fins by Taranaki and East Cape, its slender tail by Auckland and Northland curving away into the Pacific and its great heart by Lake Taupo. In order to make this flat land habitable the forces of the various Maori supernatural beings (Taniwha and Atua) were called upon and, in a manner strangely reminiscent of this country's celebrated earthquakes, they began to shape the land to create mountains, hills, valleys, lakes and streams. It continues to amaze me in no small way that the ancient Maori, with no recourse to such a lofty perspective, were able to determine the fish-like shape of the North Island of New Zealand. In reality it was probably the navigational skills of these ancients, honed as they were from travelling great distances over vast oceans, that gave them the ability to map and visualise the shape of the land. In this same mythic tradition that explains the existence of these islands of New Zealand, the South Island was identified as the canoe of Maui and Stewart Island was its anchor-stone.

The Maori names by which many of the landmarks of Wellington are known, including its harbour islands, were said to be left by the great Maori navigator and explorer Kupe who visited New Zealand approximately 1,000 years ago. Like a good many explorers since and no doubt some before him, Kupe undertook his journey of discovery throughout this remarkable land identifying landmarks and naming them as he went. It is estimated that Kupe named at least 60 locations within the area known as Te Whanganui-a-Tara (The Great Harbour of Tara or Wellington and its surroundings) and Raukawa Moana (Cook Strait). The names given by Kupe to the islands of Wellington Harbour were for members of his family and were, in the main, female names. Makaro (Ward Island) was named for a grandaughter or grandniece, Matiu (Somes Island) for a daughter or niece, and the little island at its northern end, Mokopuna, simply means grandchild. By virtue of its position in the centre of an expansive harbour and of its terrain Matiu/Somes has, throughout the centuries, commanded an important and strategic position at once recognised by all those who saw it and understood the value of its unique isolation. Early Maori occupied the island as a secure and defensible stronghold utilising the northern end to build fortified villages or Pa, the remains of which sites are still visible on the island today. In its time Matiu/Somes has been used as a fortress, a quarantine station for both humans and animals, a place of confinement for prisoners of war and alien internees and, through the recent opening up of access to the island, as a place of peaceful refuge and contemplation from the bustle of the city.

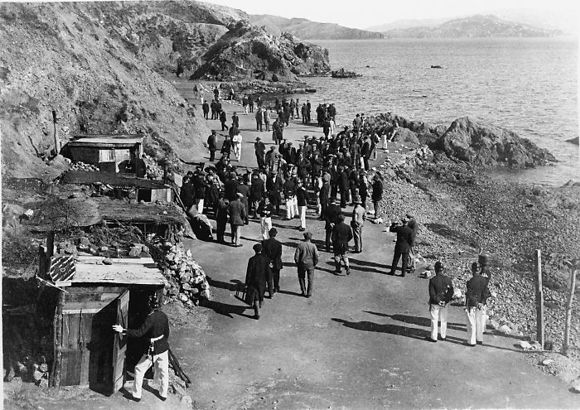

In the latter half of the 19th century, when British immigration to New Zealand began in earnest, Matiu/Somes was used as a quarantine station for those with diseases which posed a threat to the existing population of Wellington. In the early days of the city quarantine grounds had been set up at Kaiwharawhara on the western shore and later at Oriental Bay on the eastern side of Lambton Harbour. Soon, however, it was acknowledged that the isolation of Matiu/Somes would furnish the colony with protection from dangerous diseases such as scarlatina, yellow fever, smallpox, whooping cough, dysentry, tuberculosis and measles and on December 21st 1868 the location of the quarantine station was moved to Matiu/Somes. The illnesses from which Matiu/Somes protected the fledgling nationwere would be brought into the country from Britain and Europe aboard the closely packed immigrant vessels which often carried upwards of 300 to 400 immigrants and thus became excellent breeding grounds for communicable diseases. Although great care was taken at the boarding depot to check all passengers before allowing them to board the ship, it happened from time to time that immigrants went to great lengths to conceal an illness from the eyes of the Surgeon Superintendent to ensure they and their families would be able to embark. If undetected such diseases would often race through a ship taking the lives of many including, in particular, those with little resistance such as children and infants. Stringent laws were put in place to ensure that these diseases did not take hold in New Zealand and it was required that vessels arriving from overseas be inspected by the Port Health Officer prior to touching land. Any vessel arriving with a known infectious disease on board was required to enter port flying a yellow flag and to anchor near the quarantine station to await the decision of health authorities. In some cases Matiu/Somes became a permanent home as some immigrants, not many, died as a result of their illness. The island remained as a human quarantine station until 1920 and a memorial there records the names of 39 who died on the island between 1872 and 1919 and who were buried in its small cemetery. Most notably amongst these names is that of Kim Lee a chinese fruiterer from Wellington who was thought to have been suffering from leprosy and, as such, was confined to tiny Mokopuna Island off the northern tip of Matiu/Somes. Although Mr Lee was provided with adequate supplies sent over to him by flying fox from Matiu/Somes he was not to survive for long and passed away after living in a cave for three months on this tiny, exposed scrap of rock leaving the island with the local nickname of "Leper Island" to record his brief presence there.

For centuries before the arrival of European settlers in Wellington Harbour, Matiu/Somes was recognised as a natural fortress. Its highest point, towering 76 meters above sea level, possessed a commanding view over the harbour and with its naturally occurring defences the island became the most obvious place for a fortress overlooking the harbour. As has been mentioned, early Maori built fortified villages on the island and used its isolation to escape in times of peril. Also realising the value of the island as a stronghold, British settlers utilised Matiu/Somes (or Somes Island as it was called from 1840, named for Joseph Somes, a director of the New Zealand Company), as a location for the establishment of a gun emplacement and its associated powder magazine in 1840. Colonel William Wakefield, brother of colonial visionary Edward Gibbon Wakefield, father of New Zealand, concluded in a letter to Joseph Somes dated April 1840, "I have built a capacious powder magazine, and shall want the four eighteen-pounder guns from the Adelaide on the summit of Somes Island." This powerful battery of great guns would have been a threat to contemplate had anyone decided to attack the fledgling city through the harbour entrance or across its tranquil waters. The earthquake of 1855 raised and exposed the coastal platform of Matiu/Somes increasing the amount of dry land that could be utilised and much of this coastal platform has been used for a round-island coastal road. In World War Two the threat of Japanese forces rampaging towards the South Pacific, brought about the establishment of concrete gun emplacements on the summit of Matiu/Somes with four 4.7inch anti-aircraft guns manned by fifty troops. During both World Wars Matiu/Somes was used as an internment camp for resident aliens, those considered to be of foreign nationality, and some genuine prisoners of war. During World War One a number of those of German, Austrian, Bulgarian and Turkish descent were detained by force on the island and, from 1918, this number included some of the crew of the German raider Seeadler in addition to its Captain Count von Luckner who some considered to be a spy. As similar uneasiness occurred during World War Two and led to the detention of some 300 New Zealanders of German, Italian, Finnish and Tongan descent and their internment on the island. Many greatly resented this treatment as they saw themselves as loyal New Zealanders, residents going back several generations. As much as I would like I cannot explain the actions of our then government, however I believe that where a state of war exists between two countries, those who may yet harbour sympathies for the enemy country or with their political ends must be detained until hostilities have ceased and perhaps at this time considerations of forgiveness and apology may be heeded.

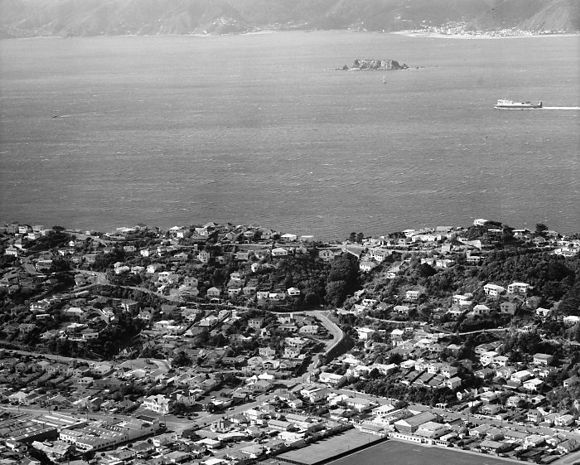

Since 1889, in conjunction with its use as a human quarantine station, Matiu/Somes was designated as a quarantine station for imported stock along with Quail Island in Lyttelton Harbour (Christchurch) and Motuiti Island in the Waitemata Harbour (Auckland). In 1908 Matiu/Somes was chosen to be New Zealand's primary quarantine station and in the 1960's, when Patrick and I were on the island, a maximum quarantine station was in the process of being built to replace the run-down facilities left over from the previous century. I recall the huge concrete buildings lined with linoleum to make cleaning easier. Within these buildings Patrick and I marveled at the echoing, catherdal-like sounds we could make. More than once we pushed each other around the corridors on a small trolley and, on one occasion, ran into the linoleum lining cracking it open. Of course nothing was said about that incident by either of us. The later advent of artificial insemination as a viable stock reproducing alternative to importing live animals side-lined the need for a maximum quarantine station in New Zealand and Matiu/Somes and its little off-shoot, Mokopuna (Leper Island) have since become wildlife sanctuaries providing a protected habitat for native birds and lizards. Tuatara, that ancient inhabitant of New Zealand older in its lineage than the dinosaur, had been present on the island until the 1870's when they died out but have recently been re-introduced and are thriving. Once heavily forested Matiu/Somes became a barren and windswept island, but through the intervention of those who care the island vegetation has been re-established as part of a planned series of annual plantings by a local branch of the Forest and Bird Protection Society, commencing from the early 1980's. Today the island is open to visitors, however access is strictly controlled and in such conditions as presently exist (the extremely dry weather conditions of February/March 2008) free access is suspended due to the threat of fire.

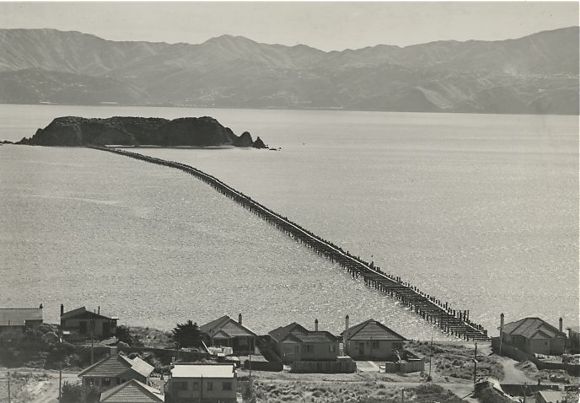

Almost as an addendum to this story we turn to the small, rocky sibling of Matiu/Somes some 5km to the south east. Makaro or Ward Island as it has been known since the time of European colonisation, has had almost none of the glory, romance or human interaction showered on its larger sister but has in the past played its part in the history, life and times of Wellington Harbour. As part of the up-thrust ridge that continues northward to become Matiu/Somes and Mokopuna Islands, Makaro/Ward is barren and almost devoid of vegetation. Like Matiu/Somes she wears a skirt of flat land thrust up by the 1855 earthquake which has become shingle beach in places interspersed with rock ledge and steep cliffs. Standing some 20 meters above the water, Makaro/Ward is a relatively barren rock with an almost impenetrable growth of native taupata (coprosma) across its upper surfaces. The island is a popular destination for recreational watercraft of all kinds and the reefs and rocky coastline provide good fishing and snorkelling opportunities. Off the southern end lie beds of seaweed providing shelter for abundant fish life, and opportunities for collecting edible shellfish such as paua (New Zealand abalone) and green lipped mussels abound. During the early 19th century the island provided a place of refuge for Ngati Ira (a local Maori tribe) from other marauding tribes, and in World War 2 it was used as an anchor point for an anti-submarine /anti-shipping barrier to reduce the effective width of the harbour and make it more easily defensible should that need arise. As shown in the picture below a wooden boom composed of two rows of wooden piles, set 6 feet apart and joined at the top by horizontal beams, extended out from Robinsons Bay in the suburb of Eastbourne. This harbour protection was continued across to Kau Point on the western shore of the harbour with a net suspended from bouys reaching out from the western side of Makaro/Ward. By this means some 6.4 kilometers (convert) of protection was provided from submarines and enemy shipping but apart from a few concrete blocks on the western side of the island no remains of these extensive structures can be seen today. Makaro/Ward is now a Government reserve managed by the Department of Conservation, and camping is not permitted. The island and water around it is mainly used by recreational divers and fishers and the island itself it is frequented in the main by seabirds.

© Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |