|

Zeitblick

/ Das Online-Magazin der HillAc -

1. Juni 2008 - Nr. 29

|

|

City, My City |

|

|

Series 3, Part 2 Shaken, Not Stirred It would be very wrong to say that Wellingtonians, and most citizens of New Zealand, are inured to the feel and effects of earth movements beneath their feet. Concerned about them? Certainly. Fearful of them? Almost always. But indifferent to their potential? Never. These are the very forces of nature which, together with the weather, the motion of the planets and the ebb and flow of the tides are completely out of our control. We can but prepare for the time when their power is unleashed but, unlike these others, earthquakes have very little regularity in their occurrence and are all but unpredictable. There will come a time when once again Wellington and perhaps all of New Zealand will experience "the big one" and be in awe of the Maori god of earthquakes, Ruaumoko.

Maori tradition has it that the tremors which so often shake New Zealand are created by the god of earthquakes, Ruaumoko. He is one of the sons of the sky father Ranginui and the earth mother, Papatuanuku. When Ranginui was separated from Papatuanuku they both shed copious tears and were very aggrieved. So that husband and wife should not witness each others sorrow their sons turned Papatuanuku over but the youngest of the sons, Ruaumoko, was still at his mothers breast and was trapped beneath her in the underworld. To ensure that he was kept warm Ruaumoko was given fire and as his underground movement disturbed and shook the land and fire often issued forth he became known as the god of earthquakes and volcanoes. Nowadays, of course, we know the real reason behind the occurrence of earthquakes and have even advanced the science of being able to predict them, although this is far from accurate. Let us consider, however, that Maori legend may be the manifestation of ancient knowledge. We know that New Zealand was born of fire and titanic struggles deep inside the earth. We know that Taupo in the North Island was the scene of multiple violent eruptions over the past 300,000 years and that some 26,500 years ago in this area occurred the largest known eruption yet recorded on earth, the resulting hole forming the picturesque and serene Lake Taupo. We know that New Zealand is the peak of a volcanic ridge running north east by south west and perches on top of the juncture of two of the earth's tectonic plates. Little wonder that these islands shake, rattle and roll as they do and that this memory stretches back millennia.

New Zealand, as were many of the earth's land areas, was once part of the immense continent known as Ur. Over measureless aeons this continent broke up and part of it formed Gondwanaland, the great southern continent. Eventually Gondwanaland broke up to form Africa, India, Antarctica, Australia and, more recently, the undersea continent of Zealandia of which New Zealand is one of several visible portions. The shape of New Zealand roughly follows the gentle curve of the junction between the Australian and Pacific plates, arching along the South Island, passing to the east of Wellington and following the eastern coastline of the North Island before charging off into the Pacific Ocean. In the very south of the South Island and beyond, the Pacific Plate rides up and over the Australian Plate. Along the ridge of the South Island, forming the Southern Alps, the plates butt together while in the north the Australian Plate forces its way over the Pacific Plate. Many fault lines - cracks in the outer crust of the earth which give vent to the great forces at work there - occur at this meeting point of the plates and a number of these may be found in and around the Wellington area. Although geological science may one day discover more, there are presently 5 identified fault lines passing through the Wellington region. The Wellington Fault, the main one to the west of the capital, is the longest continuous fault line in New Zealand stretching from south of Wellington up through the length of the southern and central North Island to the Bay of Plenty in the north east. It is the periodic movement of these 5 fault lines which over centuries, millennia, has served to shape and make the Wellington we know today.

Future advances in geological science may possibly push back the boundaries of our understanding of the birth of our city, however present knowledge accepts that movement in the Wellington Fault some one and a half million years ago caused a rupture to the west of the present harbour sending its eastern portion plunging downward and its western flank up to form a long steep ridge which has become the present day western hills of Wellington. Of the resulting series of basins formed by this upheaval the southern-most, and deepest, was to form the depression that became our present-day Wellington Harbour. Additional violent movement occurred millennia later resulting in further alteration to the shape of the harbour. The neck of land now known as the Miramar Peninsula (centre-right in the picture above) was initially detached from the mainland and known as the island of Motukairangi. In the 15th century an immense movement of the fault line which sweeps out into the harbour raised the sea floor between what was Motukairangi Island and the mainland. This elevation, known to Maori of the time as Haowhenua, or the land swallower, formed a swampy but relatively dry isthmus joining the island with the mainland and completely altering the dual entrances to the harbour. The isthmus was further raised by the great earthquake of 1855 (magnitude 8) and is now the location, on its eastern boundary, of Wellington International Airport.

With the arrival of the New Zealand Company in Wellington earthquakes in and affecting the region have been better recorded but must still have been of great concern to those arriving from a country where the earth never shook. The alarm and panic accompanying even a small earthquake let alone the mighty shake that occurred within 8 years (1848) of the arrival of the first settlers would cause many to wonder at their decision to emigrate to the ends of the earth. Then to have the whole experience duplicated only 7 years later (1855) would surely have caused lesser mortals to retreat to a safer place such as Australia or to return to England. Indeed, some settlers did just that but many remained, realising that, while New Zealand experienced many small tremors, the really big shakes were few and far between. The early settlers experienced their first tremor in May 1840 several weeks after they arrived. This occurred immediately following a disastrous fire which destroyed a row of rough reed and flax dwellings named "Cornish Row" during which many families lost their meagre possessions. The report of this earthquake may be seen in the newspaper of the day, the New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator: "The excitement of the fire had hardly ceased, when the Colonists were roused by an undulatory motion of the earth, and a somewhat severe shaking of their houses"..."The first movement took place at about twenty minutes to five o'clock in the morning of the 26th of May; the second about an hour later"..."The first shock was by far the severest and longest in duration; - it was not, however, the cause of any mischief, though it alarmed some of the inhabitants". A few months earlier the settlers had experienced a flood when the Hutt River overflowed its banks. The settlers had thus, within a few short months, experienced flood, fire and earthquake. Perhaps they wondered what was to come next - and they wouldn't be disappointed.

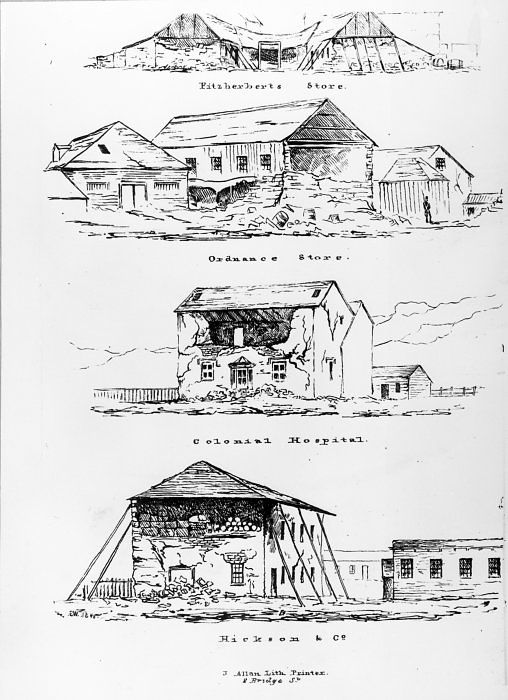

Now comfortably established on the southern shores of the Harbour between Thorndon and Te Aro, the township of Wellington was well entrenched and growing rapidly. All was good, the settlement was flourishing and perhaps the natural calamities of previous years were a thing of the past. October 1848, however, was to give Wellington's 4,500 settlers much to think about. At 1:40am on the 16th of October, in the middle of a severe gale accompanied by very heavy rain, the fault line along the Awatere Valley in Marlborough, across Cook Strait from Wellington, ruptured along at least 105 kilometers of its length. The force of this breach caused the land around it to move 8 meters horizontally and gave a reading of magnitude 7.5. Violent shaking ripped through Wellington throwing down many of the more inflexible buildings and causing damage houses, the barracks, the jail and the colonial hospital as well as numerous commercial buildings and churches. It seemed that the materials used for construction in the old country, brick and stone, would not be suitable here in Wellington. Remarkably many of the wooden dwellings of the township, being more flexible, survived the tumult whilst still losing their brick chimneys. Significant aftershocks, occurring the next day and three days later on October 19th, brought down a number of the previously damaged buildings and many residents felt that these aftershocks were equivalent to or stronger than the initial earthquake. As the aftershocks continued many sought the assumed safety of ships in the harbour and on October 26th about 60 settlers sailed for Sydney, Australia on board the barque Subraon. Unfortunately Subraon never made it to the harbour entrance and was wrecked while trying to negotiate Chaffers Passage, but without loss of life. Many of those rescued from the Subraon decided to remain in Wellington and official concern about the future of the city gave rise to the following government proclamation: "In consequence of the wreck of the 'Subraon', and from a hope generally experienced that the earthquake is now nearly over, I believe that many who had intended to quit the Colony will remain. I would hope that even the injury which the Colony is likely to sustain by the impression which the occurrence of so severe an earthquake must naturally make in England, will not be so great or so permanent as was at first anticipated". Thankfully the 1848 catastrophe took only three lives but these were all from the same family. Barrack Sergeant Lovell and his two children, a daughter aged 8 and a son aged 4 were in Farish Street (now Victoria Street) at the time of the earthquake and a brick wall collapsed on top of them. The young girl died at the scene while her little brother died from his injuries at 11pm the following day. Sergeant Lovell perished some time later and was buried with military honours on October 20th 1848.

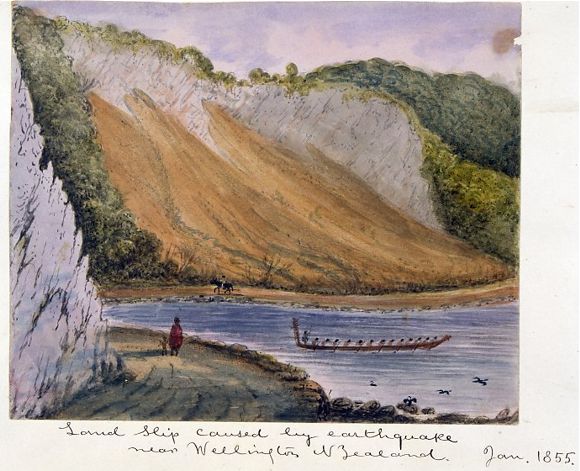

The anniversary of the founding of Wellington is recognised on January 22nd each year and is recognised as a public holiday: at least for the Wellington region. Such was the case on January 22nd and 23rd 1855, 15 years after the first settlers had landed. Wellingtonians were winding down after a two-day holiday when, at about 10 minutes past 9 in the evening, the Wairarapa Fault along Palliser Bay to the east of Wellington ruptured along 140 kilometers of its length causing the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in New Zealand - magnitude 8.2. During the day of the 23rd there had been strong winds and heavy rain but both ceased as evening approached and it became still and calm. The main shock lasted for at least 50 seconds (2 minutes according to the newspaper of the day) during which time many fled outdoors where they opted to remain for the night finding solace in tents and makeshift beds. Incessant aftershocks continued to rock the area, one diligent citizen counting 250 of them in the 11 hours following the main jolt. Although many buildings had been re-built in wood following the big shake of 1848 some new business premises were constructed in brick because of the risk of fire and it was these that received the most damaged. As was mentioned in the New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator at the time: "The injury which has been occasioned to the buildings in the town was caused by the first shock"..."but this has been very considerable, chiefly among buildings of a substantial class, constructed of brick; of these the bank has suffered the most, the gaol has also received damage; the wooden building have mostly escaped without injury" Deaths from this earthquake were recorded as being between 5 and 9, the most notable, and only death occurring in Wellington, being that of local character Baron Charles von Alzdorf. Following the 1848 earthquake the Baron had determined that if he built his hotel from brick then no earthquake could bring it down. It was, in fact, within this very structure and because of the earthquake that he met his death. Some months earlier he had suffered from the debilitating effects of an "apoplectic stroke" and he had been sitting in one of the hotel rooms. The chimney collapsed causing parts of the fireplace to fly out and strike him and he died instantly. Unlike the 1848 earthquake land movement, particularly upwards, was a key feature of the 1855 shake. A new periphery of beach and rock was created along the Wellington coast and many jetties along the shore became unusable. For instance John Plimmers bond store and warehouse (Plimmers Ark) constructed from the shell of the beached ship Inconstant was left high and dry. Plimmer had no choice but to brace up the hull, build the earth up around it and construct a longer jetty to reach deeper water. So much land was raised in 1855 that several blocks of Wellingtons present day central business district occupy land which, prior to 1855, was under water. The Hutt Road, which had previously been impassable at high tide, was made more substantial because of land raised in the 1855 shake, enough being raised to allow for the construction of a wider road and a railway line. Approximately 5,000 square kilometers of land west of the fault, towards Wellington, was lifted up and tilted and for a time a tsunami sloshed around Wellington Harbour causing the tide to appear to rise and drop every 20 minutes. Such was the amount of land that was brought up the Basin Reserve, originally to have been an inland shipping basin reached by a broad canal, was left as dry land and became Wellingtons cherished cricket ground. And the canal? It has become the broad parallel streets Kent Terrace and Cambridge Terrace leading too and from the Basin Reserve - boy racer territory after dark.

Since those immense earthquakes of 1848 and 1855 there have been no such severe shakes felt here in Wellington. The Wairarapa earthquakes of June and then August 1942, felt quite keenly in Wellington, were thought by many to be attacks by Japanese forces. Damage did occur in Wellington from these earthquakes and one person died but because they were quite deep the effects were less brutal than the shallow quake of 1855. Over the decades there have been severe and destructive earthquakes in Napier (1931), Inangahua (1968) and Edgcumbe (1987), all of which were felt in Wellington. Whilst tremors are something we New Zealanders get used to at a very yearly age, and usually many times a year, within my lifetime there have been no major Wellington shakes to worry about. One does wonder, though, as the ground shakes and the building sways if this is indeed to be "the big one". There are many types of tremors from the slow gentle sway to the short sharp shock and even those which, like a truck approaching from a distance, you can hear coming. I would not wish to experience a violent and destructive earthquake but then neither would I wish this experience on my grandchildren as it is something completely beyond ones control and arguably the most terrifying natural phenomena to experience. We were always taught to crawl under a table or desk or stand in a doorway but in a large shake even this action would probably be futile. Let us ask Ruaumoko to be still for a few more centuries yet.

© Peter Wells, Wellington, New Zealand |